What is the harvest moon?

Harvest Moon is the full moon that occurs nearest the date of the autumnal equinox, September 22. Since this is harvest time, the name harvest moon has become general. At this time of year the moon is traveling at the least possible angle with the ecliptic, and rises at about the same time on several successive nights, and shines with unusual brilliance. While the harvest moon has often been the inspiration of poet and painter, it also serves the practical purpose of furnishing the agriculturist with light strong enough to work by at the season when time is precious.

Antibiotics in the 20th century

Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928. Penicillin stopped the growth of disease-carrying bacteria. Thus it could help cure illnesses caused by these bacteria. In the years after Fleming's discovery, other substances were discovered to have similar effects. Streptomycin, which was discovered in 1944, attacked bacteria that could resist penicillin. All of these substances are called antibiotics, and after 1945 they transformed the fight against disease. They cured certain illnesses, such as tuberculosis, that previously could not be treated, and they made surgery safer from infections. Antibiotics were also used to improve the health of animals that are used for food. Although some bacteria came to resist antibiotics, these substances became essential in reducing sicknesses and providing more food.

What is homeopathy?

HOMEOPATHY is a system of medical practice based on a theory of Dr. Samuel Hahnemann of Leipzig. He practiced this system about the beginning of the 1800's. He called it homeopathic to distinguish it from the older school of medicine, which he called allopathic.

Hahnemann's theory was that a drug which will produce certain disease symptoms in a healthy person will cure a sick person who has the same symptoms. He expressed this in the Latin phrase, Similia similibus curantur, which means like cures like.

In spite of opposition by the leading physicians of his day, Hahnemann became noted and had many followers. Homeopathic medical schools, clinics, societies, and journals sprang up in various cities in Europe and the United States.

Hahnemann's theory was that a drug which will produce certain disease symptoms in a healthy person will cure a sick person who has the same symptoms. He expressed this in the Latin phrase, Similia similibus curantur, which means like cures like.

In spite of opposition by the leading physicians of his day, Hahnemann became noted and had many followers. Homeopathic medical schools, clinics, societies, and journals sprang up in various cities in Europe and the United States.

Helen Hunt Jackson

Helen Hunt Jackson (1831-1885) was an American writer. Her maiden name was Helen Fiske. She was born at Amherst, and died at San Francisco. In 1853 she married Captain Edward Hunt, with whom she traveled extensively in the West, gathering the material afterward used in her stories and poems. In 1863 Captain Hunt died. Her second husband, W. S. Jackson, was a banker. She adopted "H. H." as a pen name. She interested herself in the cause of the Indians. A Century of Dishonor, appearing in 1881, was a sharp rap on the United States government for not taking better care of the natives. In 1884 her best story, Ramona, appeared. The scene is laid in California, It has been called "The Uncle Tom's Cabin" of the Indians. It was intended by the writer to attract public attention to the injustice suffered by the Indians. It won fame for the writer and still ranks as one of the greater American tales. She wrote several other novels and made many contributions to periodicals; but Ramona and a number of lovely lyrics are her title to fame. Some of the latter, as September and October, are sure to be found in every volume of children's verse.

Jacob's Ladder plant

The Jacob's Ladder is a familiar garden plant of the phlox family. The stem is erect, from one to three feet high. The name is derived from the regular order in which nine to twenty-one leaflets are arranged on the long leaf stem. The stamens and style are exserted beyond a bright blue, bell-shaped corolla. In the northeastern part of the United States, the species is found wild only on mountains and in swamps, but it is abundant in the meadows of the Rocky Mountains and far northward.

The Jacob's Ladder plant is also known as Charity.

The Jacob's Ladder plant is also known as Charity.

What is homeostasis?

Homeostasis is the ability of an organism to maintain a stable condition within its body. This stable infernal environment is regulated by such body processes as respiration, circulation, and balance of body fluids. The nervous system and the hormones (chemicals) of the endocrine system (gland system) greatly influence homeostasis. All living things maintain some balance of internal conditions.

Scientists believe that homeostasis indicates the degree of evolution (gradual development) of a species.

The steadier an organism's internal systems, the more independent it is of the external environment. In turn, the more independent it is of its external environment, the more highly developed it is.

Scientists believe that homeostasis indicates the degree of evolution (gradual development) of a species.

The steadier an organism's internal systems, the more independent it is of the external environment. In turn, the more independent it is of its external environment, the more highly developed it is.

Ships of the Vikings

When the Europeans of the 9th century prayed to the Lord "From the wrath of the Norsemen . . . deliver us," they had good reason to pray. The Norsemen, or Vikings, as they are often called, sailed out of the harbors of Scandinavia in their swift longboats for some two centuries. Their purpose was to raid and rob the richer lands to the south and southeast.

The Vikings were as good sailors as they were shipbuilders. Their drakkar was a longboat with a dragon on its prow and a large decorated single sail. Some 16 oarsmen sat on either side of the ship helping it to move through the waters from the coast of England as far south as Spain and Italy. The drakkar's "sister" ship was the snekkar, a somewhat larger boat with a snake as a figurehead on the prow.

The Vikings' raids took them to the British Isles where they succeeded in settling forces at the mouth of the Thames River. From this and other bases they sent forces to raid London, Paris, and Dublin. They left a permanent memorial in France where the region of Normandy takes its name from the Normans, or Norsemen, raiders and settlers of old. More distant voyages took these hardy sailors to Iceland, Greenland, and, in about the year 1000, to North America. Halfway round the globe Viking traders could be found sailing south along the rivers of Russia to trade their fur and amber for the silver, spices, and brocades of the region.

The Vikings were as good sailors as they were shipbuilders. Their drakkar was a longboat with a dragon on its prow and a large decorated single sail. Some 16 oarsmen sat on either side of the ship helping it to move through the waters from the coast of England as far south as Spain and Italy. The drakkar's "sister" ship was the snekkar, a somewhat larger boat with a snake as a figurehead on the prow.

The Vikings' raids took them to the British Isles where they succeeded in settling forces at the mouth of the Thames River. From this and other bases they sent forces to raid London, Paris, and Dublin. They left a permanent memorial in France where the region of Normandy takes its name from the Normans, or Norsemen, raiders and settlers of old. More distant voyages took these hardy sailors to Iceland, Greenland, and, in about the year 1000, to North America. Halfway round the globe Viking traders could be found sailing south along the rivers of Russia to trade their fur and amber for the silver, spices, and brocades of the region.

What is a frieze?

Frieze, strictly speaking, is that part of the entablature of a building which forms a band between the architrave and the cornice, but more freely used to designate the decoration applied to that portion. The decoration varies with the order of architecture. In Doric examples it is divided into equal sections by raised portions with three angular flutes. The fluted sections are called triglyphs, the spaces between, metopes. The metopes are sometimes left plain, and sometimes—as in the Parthenon—richly decorated. In Roman buildings the decoration frequently takes the form of oxskulls and wreaths. When not so divided, the ornament often offers a continuous design, sometimes of men and animals, illustrating some theme, oftentimes floral. Familiarly, in domestic architecture, the word frieze is applied to the band of decoration just below the cornice of an interior.

Ionic frieze

How Did The Vikings Discover America?

Among the Viking explorers was a man who was nicknamed Eric the Red because of his red hair and beard. Eric grew up in Iceland, where his father had been sent as punishment for having killed another Viking. Eric had a terrible temper, and one day he killed one of his neighbors in a fight. The Vikings declared him an outlaw and ordered him to leave Iceland for 3 years.

Eric, his family, and friends loaded their possessions on board 25 ships and sailed away. Other Vikings told them about a large island to the west, so they headed in that direction. Eventually they landed on the rugged coast of this island. Although it was mostly icy wasteland, Eric called it Greenland. He hoped the name would attract settlers, which it did.

A Viking settlement was started around A.D. 985. It lasted for about 400 years.

Eric had a son who was named Leif Ericson—also known as Leif the Lucky. Leif, too, was an explorer. Around the year 1 000, Leif and his crew were caught in a storm while sailing from Norway to Greenland. For many days they were lost at sea. At last they sighted land—the coast of North America.

No one is sure where Leif and his men first came ashore. It may have been as far north as Labrador in present-day Canada or as far south as Virginia. The Vikings described the place as being covered by vast forests, wheat fields, and grapevines. They called it Vinland, or Wineland. Other expeditions followed and settlements were built. However, the Indians later drove out the Vikings. But the fact remains that the Vikings discovered America 500 years before Columbus.

Eric, his family, and friends loaded their possessions on board 25 ships and sailed away. Other Vikings told them about a large island to the west, so they headed in that direction. Eventually they landed on the rugged coast of this island. Although it was mostly icy wasteland, Eric called it Greenland. He hoped the name would attract settlers, which it did.

A Viking settlement was started around A.D. 985. It lasted for about 400 years.

Eric had a son who was named Leif Ericson—also known as Leif the Lucky. Leif, too, was an explorer. Around the year 1 000, Leif and his crew were caught in a storm while sailing from Norway to Greenland. For many days they were lost at sea. At last they sighted land—the coast of North America.

No one is sure where Leif and his men first came ashore. It may have been as far north as Labrador in present-day Canada or as far south as Virginia. The Vikings described the place as being covered by vast forests, wheat fields, and grapevines. They called it Vinland, or Wineland. Other expeditions followed and settlements were built. However, the Indians later drove out the Vikings. But the fact remains that the Vikings discovered America 500 years before Columbus.

John Suckling

Sir John Suckling (1609-1642), was an English Cavalier poet, born in Whitton, Middlesex, and educated at Trinity College, Cambridge University. On the death of his father in 1627 he became heir to large estates. In the next year Suckling began an extended tour of the Continent, and in 1631-32 served with the forces of the Swedish king Gustavus II in defense of the Protestant cause. In 1641 he took an active part in the abortive plot to rescue Sir Thomas Wentworth, the pro-Royalist Earl of Stafford, from the Tower of London, in which he had been imprisoned at the time of the Great Rebellion. As a result of his complicity in the plot, Suckling was forced to flee to the Continent. Impoverished and in despair, he is said to have poisoned himself in Paris in the summer of 1642.

Suckling's works, few of which were published during his lifetime, were collected under the title Fragmenta Aurea ("Golden Fragments". 1646). The volume contains three plays. Aglaura (1637), The Goblins (1638), and Brennoralt, or the Discontented Colonel (1639); a theological tract titled An Account of Religion by Reason; and miscellaneous poems. In a later edition (1658) appeared an unfinished tragedy, The Sad One. Suckling's fame depends entirely upon his lyrics, which are distinguished for their grace and gaiety.

Suckling's works, few of which were published during his lifetime, were collected under the title Fragmenta Aurea ("Golden Fragments". 1646). The volume contains three plays. Aglaura (1637), The Goblins (1638), and Brennoralt, or the Discontented Colonel (1639); a theological tract titled An Account of Religion by Reason; and miscellaneous poems. In a later edition (1658) appeared an unfinished tragedy, The Sad One. Suckling's fame depends entirely upon his lyrics, which are distinguished for their grace and gaiety.

What is a waterbed?

| waterbed |

What is Jaundice?

Jaundice is a yellow color of the skin and eye. It arises from coloring matter in the skin which the liver, whose province it is, has failed to remove. As one whose liver is out of order is not likely to look on the world with a pleased eye, the term "jaundiced" has been applied proverbially to one who is out of sorts.

All seems infected that th' infected spy,

As all looks yellow to the jaundic'd eye.

—Pope, Essay on Criticism.

Agustin de Iturbide

|

| Iturbide |

Agustin de Iturbide (1783-1824) was an emperor of Mexico. He was a native of Valladolid, Mexico. His father was a Spanish nobleman, his mother a rich creole. When the Mexicans first attempted to throw off Spanish rule the Spanish viceroy put Iturbide in command of the militia; but, instead of putting down the rebellion, Iturbide carried the militia over to the Mexican side. In 1822 the Mexicans made him their emperor and passed a law providing that his son should succeed him. The new emperor was too despotic, however, to suit the Mexicans, or perhaps they chafed under any autocratic government. In less than a year Iturbide was banished and went to Leghorn, Italy, to reside, with a pension from the Mexican Congress of $25,000 a year. A few months later Iturbide went to London. In 1824 he sailed for Mexico to recover his lost sovereignty. He landed July 14, and issued a proclamation that he would govern in accordance with the constitution and usages of England. July 17 he was arrested, and July 19 he was shot as a disturber of the public peace. The Mexicans settled a pension on his family.

Thomas Sully

|

| Decatur by Thomas Sully |

What is the Society of Friends?

|

| Colonial Quakers |

The "Green Revolution"

As a result of intensive research, scientists in the 1960's discovered ways of producing seeds that yielded much more rice and wheat than ever before. The new seeds were also improved by the use of better fertilizers and by advances in the techniques of irrigation.

The ability to feed large numbers of people became increasingly critical as the world's population grew (currently stands at 7 billion). Unfortunately, most of the fastest-growing countries were also the poorest and the least able to feed themselves. In the 1980's, for example, Ethiopia was unable to cope with the long period of drought and famine that plagued the country, and millions of people starved to death.

The ability to feed large numbers of people became increasingly critical as the world's population grew (currently stands at 7 billion). Unfortunately, most of the fastest-growing countries were also the poorest and the least able to feed themselves. In the 1980's, for example, Ethiopia was unable to cope with the long period of drought and famine that plagued the country, and millions of people starved to death.

Where is Ithaca (Odyssey) located?

Ithaca is one of the Ionian Islands, situated west of Greece and east of Cephalonia, from which it is separated by a narrow channel. Its area is about 38 square miles, the surface being mountainous and the coast steep and rocky. Vineyards and olive and other orchards cover the mountain sides. Fishing is carried on by the inhabitants, another industry being the production of olive oil. Its population is about 3,040 (2001).

Ithaca is supposed to be the site of the castle of Ulysses, the principal character in Homer's Odyssey. Excavations were made by Schliemann in 1869, which corroborated sites named by Homer.

Ithaca is supposed to be the site of the castle of Ulysses, the principal character in Homer's Odyssey. Excavations were made by Schliemann in 1869, which corroborated sites named by Homer.

Ulysses

What is a Jack-o'-Lantern?

Jack-o'-Lantern is a lantern carried by children, especially after nightfall Hallowe'en. It is made from a pumpkin by cutting holes to represent a mouth, nose, and eyes. A candle placed within gives a peculiarly weird light. The name is also applied to the Will-o'-the-wisp,or ignis fatuus.

Jack-ó-Lantern

Jade mineral

|

| Jade nephrite |

Jade was used by prehistoric races for ornaments, weapons, and various utensils, specimens of which have been found among the relies of the lake-dwellers of Switzerland, and of other primitive peoples. It is believed that the Jade was brought to Europe, however, as it is not found native to that country, but in the Far East. The best-known locality for jade is eastern Turkestan. The Chinese and Japanese use it largely for carved vases and bowls, for boxes and for various kinds of jewelry. They also use it in making implements.

The word jade is from the Spanish and is part of a phrase meaning "stone of the side," so named because of a belief that this mineral would cure pain in the side, or colic.

Water Colors

Water Colors are pigments prepared for the use of artists and others by mixing coloring substances in the state of fine powder with a soluble gum such as gum arabic. These are made up in the form of small cakes, which are rubbed down with water and applied with a brush to paper, ivory, and some other materials. Moist water colors are made up with honey or glycerin as well as gum, and are prepared so as to be kept in small earthenware pans or metal lie tubes. Dry cakes require to be rubbed down with water on a glazed earthenware palette or slab, but moist colors can be mixed with water for use by the friction of a brush, so that the japanned lid of the box which contains them serves for a palette. The latter are accordingly very convenient for sketching from nature.

In water-color painting two methods are employed; by one the artist works in transparent colors, by the other in opaque or body colors. In working by the latter method, which somewhat resembles on painting in its nature, Chinese white is mixed with light colors to give them body. Not only is there much artistic work done solely in transparent colors, but it is almost always these that are used for tinting mechanical drawings, maps, and the like. Some artists freely combine transparent, semi-transparent, and opaque colors. The quick drying of the water-color pigments is favorable to rapid execution; and greater clearness is attained than is practicable in oils. In water-color painting the texture of the paper employed is often of importance. Water-color drawings are of course more easily injured by damp than oil painting.

In water-color painting two methods are employed; by one the artist works in transparent colors, by the other in opaque or body colors. In working by the latter method, which somewhat resembles on painting in its nature, Chinese white is mixed with light colors to give them body. Not only is there much artistic work done solely in transparent colors, but it is almost always these that are used for tinting mechanical drawings, maps, and the like. Some artists freely combine transparent, semi-transparent, and opaque colors. The quick drying of the water-color pigments is favorable to rapid execution; and greater clearness is attained than is practicable in oils. In water-color painting the texture of the paper employed is often of importance. Water-color drawings are of course more easily injured by damp than oil painting.

Waterproof Materials

Waterproof Materials are any substances used to prevent infiltration of water or (inaccurately) other liquids. Typical waterproofing materials, all having commercial uses, are tar, oils, rubber, asbestos, asphalt, oil paints, aluminum hydroxide, metallic soaps, waxes, paraffin, resin, varnish, and cellophane.

Tar is used for caulking wooden boats and for waterproofing ropes, roofs, tarpaulins, and roads. Asbestos is likewise used for roofs, and asphalt has similar uses for roads. Asphalt varnishes are also used for protecting iron from weathering. Oils are used both as film in protecting machinery from water vapor and in impregnating fabrica, as raincoat cloth, instrument cases, and oiled shoes. Oils are also the solvent in most paints and bind the particles of pigment into a thin, resistant layer. Rubber may be used in sheet form as a cover, but it is usually vulcanized to a fabric, which gives the rubber durability, or it is deposited by electro-chemical means into the pores of the fabric. Any water-insoluble substance may be used in place of rubber, in such connection, providing it can be conveniently precipitated. Such substances are aluminium hydroxide, metallic soaps, waxe», paraffin, resin, asphalt, tar, and varnish. To make fabrics impervious to water and at the same time to allow for ventilation, recourse is had to waterproofing the yarn and then weaving the fabric out of this yarn. An important addition to the family of waterproof materials is cellophane, a cellulose product from which umbrellas, wrappings and raincoats are made.

Tar is used for caulking wooden boats and for waterproofing ropes, roofs, tarpaulins, and roads. Asbestos is likewise used for roofs, and asphalt has similar uses for roads. Asphalt varnishes are also used for protecting iron from weathering. Oils are used both as film in protecting machinery from water vapor and in impregnating fabrica, as raincoat cloth, instrument cases, and oiled shoes. Oils are also the solvent in most paints and bind the particles of pigment into a thin, resistant layer. Rubber may be used in sheet form as a cover, but it is usually vulcanized to a fabric, which gives the rubber durability, or it is deposited by electro-chemical means into the pores of the fabric. Any water-insoluble substance may be used in place of rubber, in such connection, providing it can be conveniently precipitated. Such substances are aluminium hydroxide, metallic soaps, waxe», paraffin, resin, asphalt, tar, and varnish. To make fabrics impervious to water and at the same time to allow for ventilation, recourse is had to waterproofing the yarn and then weaving the fabric out of this yarn. An important addition to the family of waterproof materials is cellophane, a cellulose product from which umbrellas, wrappings and raincoats are made.

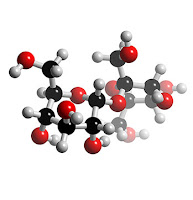

What is sucrose?

Sucrose, or saccharose, is a sugar, C12H22O11, which, together with lactose and maltose, belongs to the important group of carbohydrates known as disaccharides. It is soluble in water, slightly soluble in alcohol and ether-, moderately soluble in dilute alcohol, and crystallizes in long, slender needles. Sucrose is dextrorotatory, rotating the plane of polarized light to the right. Upon hydrolysis, it yields a mixture of glucose and fructose, which are levorotatory, turning the plane of polarized light to the left. Thus the mixture obtained is known as invert sugar, and the process is known as inversion. Inversion is carried on in the human intestine through the aid of the enzymes invertase and sucrase, metabolism of Sucrose is extracted chiefly from sugar cane and sugar beet, and is commonly called "cane sugar". When heated to temperatures above 180 °C. (356 °F.), sucrose becomes an amorphous, brown, syrupy substance called "caramel", which is used as a coloring matter in baking.

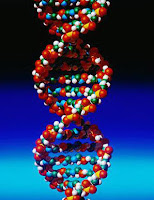

Genetic research

In 1962 the Nobel Prize in medicine, the most honored scientific award in the world, was given to an American and two British scientists. What they had discovered, in the 1950's, was the structure of DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid), an essential component of genes. As you already know, genes are the small units of chromosomes that convey characteristics, such as color of hair and eyes, from parent to child. By understanding DNA, one can understand how a gene is structured—what scientists Call the "genetic code."

By unraveling the genetic code, the experimenters with DNA came closer to explaining how different life forms are created. This break-through made possible new research into viruses, bacteria, human cells, and diseases such as cancer. Scientists found it possible to reproduce life forms in the laboratory. Major advances in treating illness were anticipated.

By unraveling the genetic code, the experimenters with DNA came closer to explaining how different life forms are created. This break-through made possible new research into viruses, bacteria, human cells, and diseases such as cancer. Scientists found it possible to reproduce life forms in the laboratory. Major advances in treating illness were anticipated.

What is a Water Mark?

Water Mark, in ordinary language, the mark or limit of the rise of a flood; the mark indicating the rise and fall of the tide. In paper making, any distinguishing device or devices indelibly stamped in the substance of a sheet of paper while yet in a damp or pulpy condition. The device representing the water mark is stamped in the fine wire gauze of the mold itself. The design is engraved on a block. from which an electrotype impression is taken; a matrix, or mold, is similarly formed from this. These are subsequently mounted on blocks of lead or gutta-percha to enable them to withstand the necessary pressure and serve as a cameo and intaglio die, between which the sheet of wire gauze is placed to receive an impression in a stamping press. The water marks used by the earlier paper makers have given names to several of the present standard sizes of paper, as pot, foolscap, crown, elephant, fan, post.

Jean Froissart

Jean Froissart (1337-1405) was a French chronicler, born in Valenciennes. At the age of 18 he went to England, where he spent a year under the patronage of Philippa of Hainault, his countrywoman. At the age of 20 Froissart began to write his history; and having completed the first section, he began his travels (1361-1366). Returning to England, he made an excursion into Scotland about 1364. Froissart accompanied the Black Prince to Dax, and the Duke of Clarence to his marriage at Milan. He was appointed in 1369 to the cure of Lestines. In 1395 he once more visited England. In 1372 Froissart began to write his famous Chroniques, which describe events in western Europe from 1326 to 1400. It is not entirely reliable from an historical point of view, but it presents a picture of the time is unrivaled in its vivid color and its charm.

Jewellery - some facts

Jewellery, or jewelry, refers to the costly personal ornaments of gold, silver, enameled ware, and the like, usually adorned with precious stones. As produced today it consists chiefly of ma-chine-made articles, often beautiful in design but lacking the artistic touch seen in the handmade ornaments of ancient and medieval times. Of late years such schools as Pratt Institute, New York, whose students in the department of fine arts have produced very beautiful hand-made Jewellery, have done much to revive the art of Jewellery making. This is a commendable step, for its proficiency in the art of making Jewellery is a test of a nation's artistic development. A jeweler must produce the largest amount of beauty within the smallest space.

The use of jewellery is as old as civilization. Some of the ancient Egyptian work resembled greatly the Chinese cloisonne of today; that of the ancient Greeks was notable for its purity and simplicity; while that of the old Romans was more ostentatious but of less exquisite workmanship. The Renaissance produced masters in Jewellery-making as it did masters in every other art. Foremost among these great jewelers were Benvenuto Cellini and Albrecht Dürer.

The modern period is characterized by a simpler and more graceful method in mounting gems and in the designing of jewelry. During the nineteenth century the diamond was the stone in high favor; now it has made way for the pearl. For many years the jewelers of London and Paris, and the gem-cutters of Holland held first place, but now American workers have won a name abroad. The quantity of gaudy Jewellery sold today is an unfortunate reflection on popular taste. Nothing bespeaks poorer judgment as to the eternal fitness of things than the wearing of such spurious jewelry, unless it be expensive jewelry worn out of place.

The use of jewellery is as old as civilization. Some of the ancient Egyptian work resembled greatly the Chinese cloisonne of today; that of the ancient Greeks was notable for its purity and simplicity; while that of the old Romans was more ostentatious but of less exquisite workmanship. The Renaissance produced masters in Jewellery-making as it did masters in every other art. Foremost among these great jewelers were Benvenuto Cellini and Albrecht Dürer.

The modern period is characterized by a simpler and more graceful method in mounting gems and in the designing of jewelry. During the nineteenth century the diamond was the stone in high favor; now it has made way for the pearl. For many years the jewelers of London and Paris, and the gem-cutters of Holland held first place, but now American workers have won a name abroad. The quantity of gaudy Jewellery sold today is an unfortunate reflection on popular taste. Nothing bespeaks poorer judgment as to the eternal fitness of things than the wearing of such spurious jewelry, unless it be expensive jewelry worn out of place.

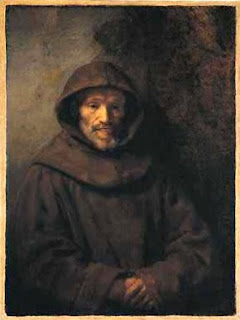

What is a friar?

Friar is the popular distinguishing title of the members of the mendicant orders. The first friars were the Franciscans or Grey Friars and Dominicans or Black Friars. To these were added the Carmelites or White Friars by Innocent IV (1224), and the Augustinian hermits or Austin Friars by Alexander IV (1256). In the 15th century the Serviles and Trinitarians or Crutched Friars were granted the same privileges as the four mendicant orders.

Franciscan friar

The Jacobin club

Jacobin is a name applied to a revolutionary club of France, and later to the party favoring democracy. When the National Assembly first met in Versailles, Lafayette, Mirabeau, and a few other Liberals formed a society known as the Friends of the Constitution. After the assembly removed to Paris, the name was changed to Jacobin club, because of their meeting in the library of the church of St. James. After the removal to Paris, the character of the club changed rapidly, the moderates dropped out, the number of members increased, and the name became synonymous with the party of extreme democracy. Daughter societies were formed throughout France, dependent on the mother club at Paris. At first the Jacobins had little influence in the assemblies though they were all powerful with the mob, but as the Revolution progressed they became more and more dominant. The Jacobins directed the attack upon the Tuilleries in 1792; they initiated the September massacres; they were the ones who insisted that Louis must die. Later when France was beset by foreign war and internal disaffection, the Jacobins instituted the Terror, which, hideous as it was, seemed a necessary evil at this time. Cruel as the Jacobin policy often was, it forms a striking contrast to the wavering vacillation of the Girondists. Every one rejoiced when in 1794 the Jacobin organization was finally suppressed after the repulsion of the foreign dangers and the downfall of Robespierre, yet it is difficult to see how otherwise the same results could have been accomplished. As Lowell says,

"They did as they were taught, not theirs the blame

If those who scattered fire brands reaped the flame."

Suite (music)

A suite, or partita, is the earliest type of musical composition containing a series of discrete sections, or movements. The suite was developed in the 16th century as a series of dance tunes, usually composed in one key.

These tunes were so arranged as to present strong contrasts between slow and fast tempos and dignified and gay moods. The four basic movements of the classical suite are: the allemande (Fr., "German"), a quiet dance in moderate tempo, composed in common time; the courante (French, "running"), a lively dance, often complex in its rhythms; the sarabande, a stately dance of Spanish origin in triple time, rich in harmonic embellishment; and the jig or gigue, a rapid and lively dance, also in triple time. A prelude, not derived from any dance form, was later customarily included at the beginning of the suite, and one or more additional dance forms, such as the minuet, gavotte, bourrée, chaconne, and passacaglia, were also sometimes inserted, generally between the saraband and gigue. The classical suite reached its perfection in the examples by the German composer Johann Sebastian Bach. In the 18th and 19th centuries the classical suite gradually merged with and was superseded by the sonata. Modern compositions called suites are only loosely related to the original form; they are primarily symphonic works, characterized by considerable freedom of structure and tonality, and cast either in abstract forms or in greatly modified dance forms.

These tunes were so arranged as to present strong contrasts between slow and fast tempos and dignified and gay moods. The four basic movements of the classical suite are: the allemande (Fr., "German"), a quiet dance in moderate tempo, composed in common time; the courante (French, "running"), a lively dance, often complex in its rhythms; the sarabande, a stately dance of Spanish origin in triple time, rich in harmonic embellishment; and the jig or gigue, a rapid and lively dance, also in triple time. A prelude, not derived from any dance form, was later customarily included at the beginning of the suite, and one or more additional dance forms, such as the minuet, gavotte, bourrée, chaconne, and passacaglia, were also sometimes inserted, generally between the saraband and gigue. The classical suite reached its perfection in the examples by the German composer Johann Sebastian Bach. In the 18th and 19th centuries the classical suite gradually merged with and was superseded by the sonata. Modern compositions called suites are only loosely related to the original form; they are primarily symphonic works, characterized by considerable freedom of structure and tonality, and cast either in abstract forms or in greatly modified dance forms.

Laser applications

In 1960 a device called a laser was invented. It could store energy and release it all at once in an intense beam of light. This beam remained straight, narrow, and very concentrated, even after it had traveled millions of miles. Its uses were extraordinarily varied—a perfect example of the combination of scientific discovery and engineering applications. Lasers were used in surgery to weld damaged tissue in the eye, to burn away skin growths, and to repair decayed parts of teeth. They were used to measure distances. A mirror placed on the moon by the Americans who landed there allowed scientists to calculate the distance to the moon more accurately than ever before.

Lasers helped engineers make tunnels and pipelines straight. They enabled manufacturers to cut precisely into hard substances, such as diamonds. Lasers also transmitted radio, television, and telephone signals. They made it possible to show three-dimensional pictures on a television or film screen. Thus one invention had effects in dozens of activities.

Freyr and Freyja, Norse gods

FREYR, or FREY, is the Norse god of rain, fertility, and peace, was, like his sister Freyja and his father Njord, a survival from the pre-Odinic mythology. His festival was at the winter solstice (Christmas). A well-known saga relates his wooing of Gerda, daughter of the frost-giant Gymir.

FREYJA is the Norse goddess of the spring, love, and fertility, sister to the god Freyr. She was often confused, and in later times identified, with the goddess-mother Frigga, the wife of Odin.

Freyr

FREYJA is the Norse goddess of the spring, love, and fertility, sister to the god Freyr. She was often confused, and in later times identified, with the goddess-mother Frigga, the wife of Odin.

Freyja

Jackstones game

Jackstones (also called jacks, fivestones, jackrocks, onesies, knucklebones, or snobs) is a game played by one or more persons with from one to five small pebbles or bits of iron. Regular iron jackstones have six knobbed prongs. The game may be played in several ways. There is tossing and catching in all of them. The five stones may be held in the palm of the hand and thrown up together and caught on the back of íhe hand. The jack may be tossed up and caught alternately on the palm and the back of the hand, the player counting five for each successful catch. The player who reaches the highest score wins. Sometimes four stones are laid on the ground. The player losses the jack and catches it, picking up a stone from the ground each time, while the jack is in the air. This method may be varied by holding the four stones in the hand and laying one on the ground between each toss and catch. Sometimes the jackstones are laid in a pile. The player arranges them in a figure, as the four corners of a square or in a straight line, this between tosses.

Lake Superior

|

| Lake Superior |

What is a harelip?

A Harelip is a cleft (split) through the upper lip. It is called harelip because it looks like the hare's lip, which is split. Doctors do not know what causes harelip. Something prevents this section of the lip from growing together before the baby is born. Harelip may be single; that is, only one side of a lip may be cleft. Or both sides of a lip may be open. Cleft palate, an opening in the roof of the mouth, often occurs with harelip. Sometimes a deformity of the nose also occurs. Doctors can successfully close these openings by means of surgical operations.

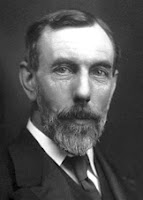

Sir William Ramsay

Sir William Ramsay (1852-1916) was a Scottish chemist who, with Baron Rayleigh, isolated the first rare atmospheric gas, argon. Ramsay also discovered the other inert gases: helium, neon, krypton, and xenon. For this work, he received the 1904 Nobel prize for chemistry. His explanation of me nature of these elements led to important ideas about atomic structure. The gases also have great practical importance.

Ramsay was born in Glasgow and studied in Germany at Heidelberg and Tübingen universities. He taught at Glasgow and Bristol, and at University College in London. He was knighted in 1902, and in 1911, he became president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Ramsay was born in Glasgow and studied in Germany at Heidelberg and Tübingen universities. He taught at Glasgow and Bristol, and at University College in London. He was knighted in 1902, and in 1911, he became president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science.

Plastics, the first synthetic substances

The first synthetic substances—substances that do not occur in nature—were developed by chemists in laboratories in the 1800's. A few of these substances began to have wide applications. For example, celluloid was used to make movie films, and bakelite was used for electrical equipment. It was not until after 1945, however, that these substances, called plastics, began to appear in every area of life. By the mid-1960's, for example, there was more synthetic rubber than natural rubber in the world.

Plastics became an essential part of daily existence. They were used to equip and furnish kitchens. They changed the way buildings were constructed and affected the manufacture of objects from toys to cars. They completely altered the appearance as well as the manufacture of most of the things people use every day, from tooth-brushes to telephones. Synthetic fibers were woven into easy-care fabrics for clothing, upholstery, and many other uses.

Many plastics were made from oil products. The production of plastics, therefore, depended on the unpredictable nature of international oil prices. Nevertheless, plastics continued to be essential to modern life in the 21th century.

What are territorial waters?

Territorial Waters are those waters which fall under the jurisdiction of a state. Rivers or lakes wholly within the boundary of a state are the property of that state. If a body of water forms a boundary between two countries, each owns half of such body, i. e., up to the middle of the part which serves such a function. If, however, such waters serve as a connecting link between parts of the high seas, they are submitted to international arbitration for jurisdiction, as in the case of the Panama Canal. Although international law does not make definite ruling to cover those uninclosed waters near the border of a country, it is generally recognized that such a country may extend its jurisdiction out as far as 3 miles. Thus the civil and criminal laws of a country are enforced over all ships both national and foreign in this strip.

The Frogs (Aristophanes)

|

| The Frogs representation |

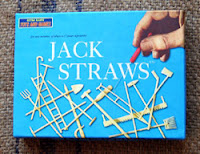

Jack Straws game

Jack Straws is a familiar parlor game. It is played with straws or with strips of bamboo, wood, ivory, bone, or the like. The straws are tumbled in a confused heap on a table. The players take turns. The first withdraws straws, one at a time, as long as he can do so without joggling the heap or moving any other straw. The right to play then passes to the next. The player who has the most straws at the conclusion of the game wins.

The pieces may be withdrawn with the finger or angled for with a hook provided for the purpose.

The pieces may be withdrawn with the finger or angled for with a hook provided for the purpose.

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is a canal 103 miles long (including 4 miles of approach channels), which crosses the Isthmus of Suez and connects Port Said on the Mediterranean Sea with Suez on the Red Sea. The Egyptian king, Rameses II, seems to have been the first to excavate a canal between the Nile delta and the Red Sea. This, having been allowed to fill up and become disused, was reopened by Darius I of Persia. It was once more cleared and made serviceable for the passage of boats by the Arab conquerors of Egypt. The French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps set himself, in 1849, to study the isthmus thoroughly, and in 1854 he managed to enlist the interest of Said Pasha, Khedive of Egypt, in his scheme for connecting the Mediterranean with the Red Sea. Two years later the Porte granted its permission and the Universal Company of the Maritime Suez Canal was formed, receiving important concessions from the ruler of Egypt.

Computers of today

|

| Pascal calculating machine |

In the 1600's, the French scientist Blaise Pascal had invented a machine that could perform arithmetical calculations. The idea intrigued scientists and engineers for the next 300 years. However, the necessary machinery was too large and cumbersome to have many applications.

It was not until the 1950's that machines capable of storing and processing information quickly and compactly were developed. These computers rapidly made an impact on society and were improved from year to year. They not only operated ever more quickly, but they required a smaller and smaller amount of space to store gigantic amounts of information.

By the mid-1980's computers performed many varied functions. They guided the flights of spacecraft and recorded every airline reservation in the world. They drew maps, kept accounts, and printed newspapers. Computers also played games with children, controlled the flow of fuel to a car's engine and solved complex mathematical questions. Problems in every field could be tackled that would have been considered impossible 60 years earlier.

What is a water thermometer?

The Water Thermometer is an instrument in which water is substituted for mercury, for ascertaining the precise degree of temperature at which water attains its maximum density. This is at 39.2 °F., or 4 °C., and from that point downward to 32 °F., or 0 °C., or the freezing point, it expands, and it also expands from the same point upward to 212 °F., or 100 °C., or the boiling point.

|

| Hot water thermometers |

Gustav Freytag (novelist)

|

| G. Freytag |

Of Freytag's dramas, Die Journalisten (1845) was one of the best German comedies of the 19th century and still remains popular. His other plays, including the ambitious tragedy Die Fabier (1859), were quickly forgotten. His dramatic criticism, Die Technik des Dramas (1863), was a synthesis of classical and modern theories which influenced many of his contemporaries. As a novelist Freytag produced one masterpiece, Solí und Haben (1855), a unique picture of German life in his time. Less distinguished, but equally known, was Die verlorene Handschrift (1864), a novel of university life.

Who were the Jacobites?

|

| Jacobites hiding |

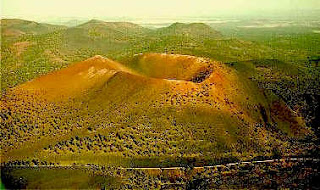

Sunset Crater National Monument

SUNSET CRATER is a national monument in Arizona, created in 1930 to preserve a notable volcanic crater. The monument covers an area of 3,040 acres in the Coconino National Forest and contains Sunset Mountain, an extinct volcano which last erupted about the end of the 9th century. The volcano is of unusual interest because of the character of the sulfuric rock at its summit. The rock, through processes of decomposition and water staining, has become reddish in color, making the mountain appear as if bathed in the rays of the setting sun. Also of interest in the area are ice caves and large cinder and lava fields.

Volcano at Sunset Crater

The beginnings of Space exploration

|

| Space Shuttle |

The main results of space exploration in the 1970's came from unmanned spacecraft. Orbiting satellites transmitted television, telephone, and radio signals around the earth, vastly improving communication. Orbiting cameras transformed weather forecasting. The American Voyager spacecraft provided important new information about the makeup of other planets.

A new phase of space exploration began with the launch of the first space shuttle, Columbia, in 1981. By 1986 reusable shuttles, which contained elements of both the traditional space capsule and the airplane, had completed two dozen successful missions. Early that year, however, the explosion of the shuttle Challenger and the lost of its crew temporarily halted the human exploration of space.

Who are the Water Spirits?

In anthropology, Water Spirits are spirits supposed to reside in lakes, rivers, and the sea. Water spirits were believed to be the active agents in all cases of drowning and shipwreck and to avenge the rescue of drowning persons on their rescuers. Hence arose the widespread superstition that it was unlucky to save a shipwrecked person or one who had fallen into the water. The belief in water spirits was almost universal at an early stage of culture and still lingers in a poetic form on the banks of the Rhine.

Nereids

Eugene Fromentin (painter)

Eugene Fromentin (1820-1876) was a French painter and writer, born in La Rochelle. He first showed artistic talent in 1840. The pictures of Marilhat, exhibited in 1844, inspired him with a passion for the East, and in 1846 he made his first visit to Algiers. His earliest Salon pictures were two Algerian sketches and a French landscape, in 1847; and after a second and third visit to Algiers Fromentin published his impressions, in Une Année dans le Sahel (1859) and L'Été dans la Sahara (1857; new ed. 1888). His Maitres d'Autrefois, a subtle critical study of the Dutch and Flemish painters, was not published until 1876.

Fromentin's paintings have definite personal charm and vivid delicate effects of color and of atmosphere, but are less scientific than the work of his noted confrères. He was an acute critic of the technique of painting, and shows keen observation and study of the effect of sunlight on color. Some of his best paintings are "Crossing the Ford," "Arabs Watering Horses," and "Encampment in Atlas Mountains."

Fromentin's paintings have definite personal charm and vivid delicate effects of color and of atmosphere, but are less scientific than the work of his noted confrères. He was an acute critic of the technique of painting, and shows keen observation and study of the effect of sunlight on color. Some of his best paintings are "Crossing the Ford," "Arabs Watering Horses," and "Encampment in Atlas Mountains."

Eugene Fromentin "Encampment in Atlas Mountains"

What is a Jinrikisha?

|

| Jinrikisha driver |

Some facts about Sunday

Sunday is first day of the week, observed by Christians almost universally as a holy day in honor of the resurrection of Christ.

The hallowing of Sunday appears incontestably as a definite law of the church in the beginning of the 4th century. The emperor Constantine confirmed the custom by a law of the state.

Throughout the medieval period the authority of the church was so universally recognized that secular legislation in this regard was almost unnecessary. The Catholic Church then required, and still requires, abstinence from servile work on Sunday, and the assistance at Mass of all who are not lawfully hindered.

In the medieval period the courts were presided over or dominated by the clergy, and Sunday early became in the legal sense a dies non, on which legal proceedings could not be conducted. By common law, however, all other business might be transacted.

The New England States were the first to regulate the observance of Sunday by a series of statutes. The Constitution of the United States prohibits the restriction of religious liberty or the enforcement of religious observances, and therefore, in law, Sunday is regarded merely as a civil day, which is a convenient one for the suspension of business, because of its observance as a holy day by a great majority of the people. These statutes are constitutional as a valid exercise of the police power. Works of necessity and great public convenience are usually excepted.

History of postal service

Postal History

|

| Post stamp |

In Europe carrier service goes back to the Roman Empire. The magnificent Roman roads were used to get messages from the provinces to the capital. The English postal service has been operating since the 1600's, when it took over the routes of the royal mail.

Over 2,000 years earlier the Greek historian Herodotus described the Persian mail service of Cyrus the Great, saying, "There is no mortal thing faster than these messengers." Marco Polo encountered a series of postal stations in China around 1300 a.d. At the same time the Aztecs in Mexico had relay stations and runners to carry the news between villages.

Mail has been getting through for a long time. Perhaps in the next century it will travel to the Moon.

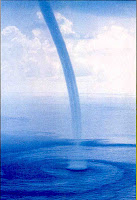

What is a waterspout?

A waterspout is a remarkable phenomenon occurring for the most part at sea, but occasionally on land, though generally in this latter case in the neighborhood of water. A waterspout at sea is usually formed in the following manner: A dense cloud projects from its center a body of vapor, in form something like a sugar loaf with the point downward. This cone is agitated by the wind till it assumes a spiral form and gradually dips more and more toward the sea, where a second cone is formed having its point upward. The clouds above and the water below are violently agitated by the physical influences at work. Suddenly the descending and ascending cones of water or vapor meet in midair and form one united pillar which moves onward vertically in calm weather, but obliquely to the horizon when acted on by the wind. The junction of the two cones is generally accompanied by an electric flash. After continuing in this form for a short time the waterspout bursts, in some cases with terrific violence and to the destruction of any-thing in the vicinity. Many a ship has been overwhelmed in this manner and sunk in a moment with all on board. In November, 1855, five vessels were destroyed by a waterspout in the harbor of Tunis. Waterspouts on land are cones or pillars of vapor descending from the clouds. Land water spouts are usually very destructive in their effects. On Aug. 30, 1878, the town of Miskolez in Hungary, was destroyed by a waterspout with considerable loss of life. These phenomena are, however, more common in India than in Europe. One which occurred at Dum-Dum, near Calcutta, was ascertained to be 1,500 feet in height, and it deluged half a square mile of territory to a depth of 6 inches.

A waterspout is a remarkable phenomenon occurring for the most part at sea, but occasionally on land, though generally in this latter case in the neighborhood of water. A waterspout at sea is usually formed in the following manner: A dense cloud projects from its center a body of vapor, in form something like a sugar loaf with the point downward. This cone is agitated by the wind till it assumes a spiral form and gradually dips more and more toward the sea, where a second cone is formed having its point upward. The clouds above and the water below are violently agitated by the physical influences at work. Suddenly the descending and ascending cones of water or vapor meet in midair and form one united pillar which moves onward vertically in calm weather, but obliquely to the horizon when acted on by the wind. The junction of the two cones is generally accompanied by an electric flash. After continuing in this form for a short time the waterspout bursts, in some cases with terrific violence and to the destruction of any-thing in the vicinity. Many a ship has been overwhelmed in this manner and sunk in a moment with all on board. In November, 1855, five vessels were destroyed by a waterspout in the harbor of Tunis. Waterspouts on land are cones or pillars of vapor descending from the clouds. Land water spouts are usually very destructive in their effects. On Aug. 30, 1878, the town of Miskolez in Hungary, was destroyed by a waterspout with considerable loss of life. These phenomena are, however, more common in India than in Europe. One which occurred at Dum-Dum, near Calcutta, was ascertained to be 1,500 feet in height, and it deluged half a square mile of territory to a depth of 6 inches.Rudolf Friml

|

| Friml |

Rudolf Friml (1881-1972) was an American composer, born in Prague. Educated at the Prague Conservatory, Friml came to the United States as accompanist for the violinist, Kubelik, in 1901. After 1906 he lived permanently in the United States, giving piano recitals and composing music. His operetta, The Firefly (1912), was followed by High Jinks (1913), Rose Marie (1916), Vagabond King (1925), The Three Musketeers (1928), The Lottery Bride (1930), and Annina (1934). In 1924 Rudolf Friml became a naturalized United States citizen. Among his piano compositions are Bohemian Dance, California Suite, Fine Mood Pictures, and Pastoral Scenes.

Ivanhoe (novel)

Ivanhoe is a novel by Sir Walter Scott. It was written about 1819, when the famous "Wizard of the North" was at his best, and appeared in print the following year. The tale combines romance and adventure. The scene is laid in England in the days of Richard I. The plot is one of the green-wood, archery, Saxon outlawry, Norman oppression, tournament, castle storming, and orderly battle. Gurth, the swineherd; Wamba, the jester; Brian de Bois-Guilbert, the knight templar; Locksley, the green-coated outlaw; Friar Tuck, the fat monk; sturdy Cedric, the Saxon; haughty Front de Boeuf; Richard Coeur de Lion, disguised as the Black Knight, are leading characters. Ivanhoe, the discredited Saxon son, is the hero; but Rebecca, a Jewish maiden, is the noblest of all. Ivanhoe is Scott's most famous novel.

Suetonius

|

| Suetonius |

After Pliny's death Suetonius was befriended by Gaius Septicius Clarus, prefect of the Praetorian Guard, to whom he dedicated his well-known work, The Lives of the Caesars. As private secretary to the emperor Hadrian from 119 to 121 B.C., Suetonius had access to imperial documents and was able to verify the facts in this work. The biographies contain information about twelve rulers of Rome, from Gaius Julius Caesar to the emperor Domitian, which is found nowhere else; much of it is in the form of scandalous anecdotes. Suetonius was the author of numerous other works now lost, including Miscellanies, an encyclopedic work on Roman antiquities and scientific subjects. His De Viris Illustribus contains biographies of poets, orators, philosophers, historians, grammarians, and rhetoricians; most of the section on grammarians and rhetoricians, and also the biographies of several poets, including those of Terence, Vergil, and Horace, have been preserved.

John Charles Frémont

John Charles Frémont (1813-90) was an American explorer, soldier, and politician, born in Savannah, Ga. After serving briefly as teacher of mathematics and engineering in the U.S. Navy, he accepted a post as civil engineer in the Army; in 1838 he was commissioned as second lieutenant of topographical engineers. He gained early fame for his western explorations; in 1842 he made an expedition to southern Wyoming, and in 1843—44 he went to the tidewater of the Columbia and thence to the Sacramento Valley. His reports on California and the Great Salt Lake region turned American attention toward both areas at a time when "manifest destiny" was guiding policy in the direction of national expansion. His third expedition (1845-47) led him to California, in whose conquest he unquestionably wished to have a part. By February, 1846, he had centered his men at San Jose, in the heart of California. The Mexican authorities ordered him to leave the country, but he refused, playing for time. He knew that war between the United States and Mexico was expected. He moved north to Klamath Lake, and then to Sutter's Fort where he encouraged the discontented American settlers in the Sacramento Valley to revolt. News of the outbreak of war reached him in July, 1846, and from then on he actively supported Commanders Robert Stockton and John Sloat in the conquest of California. At the close of the war in 1848, Stockton commissioned him civil governor of California, but Fremont was soon ousted in the bitter quarrel between Stockton and Gen. Philip Kearny over lines of authority in the new territory. As a result, Fremont was court-martialed and dismissed from the service, but President Polk remitted the sentence, allowing him to resign.

What does jingo mean?

In British politics, Jingo is a name applied to men or a party desirous of engaging in a foreign war. The term acquired this meaning during the political campaign of 1877, when there was loud talk in England of war with Russia on behalf of the Turks or really for the custody of the Hellespont. A favorite campaign doggerel of the conservatives was the following:

We don't want to fight;

But, by jingo, if we do,

We've got the ships,

We've got the men,

We've got the money, too.

The term "Jingo" is now applied in any country to those whose patriotism consists mainly in threatening other countries.

We don't want to fight;

But, by jingo, if we do,

We've got the ships,

We've got the men,

We've got the money, too.

The term "Jingo" is now applied in any country to those whose patriotism consists mainly in threatening other countries.

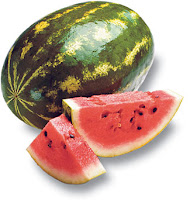

Watermelon plant

Watermelon, the Citrullus vulgaris. The plant is a prostrate, long-running, hairy vine with large leaves. The fruit is spherical or oblong, with thick, spotted green rinds; cold, watery, pink or white flesh; and black or brown seeds. It is a native of southern Africa and is now cultivated in every part of the United States and in southern France, India, China, Japan, the Eastern Peninsula, and Egypt for its juice, which is cool and refreshing, and as a dessert. Seventy percent of the crop in the United States comes from Georgia, Florida, Texas, and California. It has appeared on paintings in Egyptian tombs and in descriptions in the Old Testament. The plant of the watermelon usually requires a warm climate, but there are short seasoned varieties, such as muskmelons, which can be grown as far north as Ontario. Pickled or preserved rinds are the only by-products of the fruit.

Supersonic phenomena

Supersonics are a branch of physics dealing with the phenomena arising when a solid body exceeds the speed of sound in the medium in which it is traveling; usually the medium is air. The speed of sound in air is dependent upon several factors, including the temperature, humidity, density, and altitude. Because the speed of sound, being thus variable, is a critical factor in aerodynamic equations, it is represented by a Mach number. The Mach number is the speed of the projectile or plane with reference to the ambient atmosphere, divided by the speed of sound in the same medium and under the same conditions. Thus, at sea level, under standard

conditions of humidity and temperature, a speed of about 760 miles per hour represents a Mach number of one, that is, M=l. The same speed in the stratosphere, because of difference in density and temperature, would correspond to a Mach number of M=1.16. By designating speeds by Mach number, rather than by feet per second, or miles per hour, it is possible to obtain a more accurate representation of the actual conditions encountered in flight.

The Herschels, a family of astronomers

Sir William Herschel (1738-1822) was an eminent astronomer. He was born at Hanover, Germany. He served as a musician in the army. He came to England in 1757 and obtained employment first as a bandmaster. He employed his leisure time in studying mathematics and astronomy. In 1774 he made himself a reflecting telescope. During the American Revolutionary war, Herschel was enthusiastically engaged in mapping the heavens. George III gave him a pension enabling him to devote his entire time to astronomy. In 1787 he completed a telescope, the largest then known. It was forty feet in length and four and one-half feet in diameter. It weighed over a ton. With this instrument he discovered an extinct volcano on the surface of the Moon, two satellites of Saturn, and the planet Uranus. Herschel established the fact that Saturn's rings revolve, and made many other minor observations and discoveries. He mapped no less than 5,000 nebulae and clusters of stars new to astronomy. His sister Caroline worked with him. She herself discovered five new comets. She also drew up a catalog of the stars, and deserves to shine by reason of her own light. Sir William's work was continued by his only son, Sir John. The latter had the advantage of excellent instruments, and began work where his father left off. His first contribution to astronomical science was the study of the stars in the southern hemisphere—stars never seen by residents of the north. He spent four years near Capetown. He was made president of the Royal Astronomical Society. At his death in 1871 he was honored with burial in Westminster Abbey. The Herschels are credited with laying the foundation of modern astronomy. They began the work of mapping the heavens accurately.

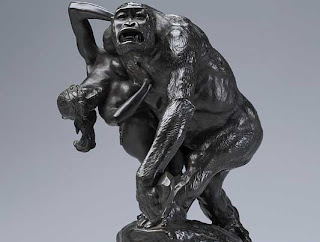

Emmanuel Frémiet (sculptor)

Emmanuel Frémiet, (1824-1910) was a French sculptor, born in Paris; pupil of Rude; was first known as a sculptor of animals. He then produced a series of statues and groups, mainly equestrian, among them "Joan of Arc" (1874), at Paris; a second "Joan of Arc" (1889), at Nancy; "Velásquez" (1891), at Paris; and "Lesseps" (1900), at the entrance to the Suez Canal. Frémiet also dealt with imaginary figures and scenes such as "Gorilla and Woman" (1887).

Emmanuel Frémiet - Gorilla Carrying off a Woman - 1887 Bronze

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)