|

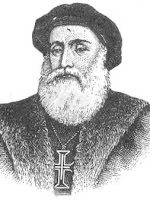

| Sir Richard Burton (1821-1890) |

Sir Richard Burton was a man of extraordinary and varied gifts. He was one of the preeminent explorers of his time, an unequaled linguist who is said to have mastered 35 languages, and the author of dozens of books on his travels and other subjects. His most famous literary achievement is a 16-volume translation of The Arabian Nights.

Richard Francis Burton was born near Elstree, England, on March 19, 1821, and taken abroad by his parents at an early age. Although he received almost no formal education, he everywhere learned the local languages and dialects. He attended Trinity College, Oxford, but was expelled, and at 21 he joined the army of the British East India Company.

In India, Burton added to his knowledge of languages, learning Hindi, Farsi (Persian), and Arabic and living with native peoples. On his first great journey, in 1853, he made a perilous trip to the Muslim holy cities of Medina and Mecca, disguised as a Muslim pilgrim. The next year he and John Speke explored East Africa, seeking the source of the Nile River. On a second expedition, in 1858, Burton discovered Lake Tanganyika. But, ill with malaria, he did not accompany Speke north and so did not share in the discovery of Lake Victoria, a main source of the Nile.

In 1861, Burton married Isabel Arundell. She was a devoted wife but had little sympathy for many of his chief interests. Burton's remaining years were spent as a British consular official, at posts around the world, exploring and writing. He was knighted in 1885. He died in Trieste (now in Italy) on October 20,1890.