THE HYDROMETER DEVICE

A hydrometer is an instrument for determining the specific gravity of liquids. It depends upon the law that a floating body displaces an amount of liquid equal to its own weight. Its most common form is a graduated glass tube with a large bulb near the lower end, below which is a smaller bulb filled with shot or mercury to make it stand upright. The lighter the liquid, the lower will the instrument sink. The density of the liquid can be read directly from the scale. Special forms for different liquids are often used, as acoholometer, lactometer, etc.

Iphigenia (mythology)

Iphigenia, in Greek legend. the daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra. When the Greek army assembled at Aulis to set sail for Troy, Agamemnon. so runs the legend, was unlucky enough to kill a stag sacred to Artemis (Diana). The soothsayer Calchas made an announcement that the offense could be appeased only by the sacrifice of Agamemnon's daughter. Agamemnon was plunged in grief, but sent for Iphigenia on the pretence of marrying her to Achilles. When the virgin was placed on the altar Artemis snatched her away and substituted a hind in her place. The maiden was wrapped in a cloud and conveyed to Tauris, where she became a priestess in the temple of Artemis.

What is Jetsam?

Jetsam is the cargo or equipment thrown overboard at sea to save a ship in distress. When a portion of a cargo is cast overboard to save a ship from foundering, or to enable it to escape from the enemy, the loss is distributed among the various owners of the cargo in proportion to the value of their shipments. Those whose property is saved are required to make up a part of the loss of him whose property is sacrificed for the general good. This is an old law of the sea.

Atalanta (mythology)

|

| Atalanta |

Even here, in this region of wonders, I find

That light-footed Fancy leaves Truth far behind,

Or at least, like Hippomenes, turns her astray

By the golden illusions he flings in her way.

Atalanta is the subject of a poem by the Roman Ovid. William Morris has also made use of the subject in his poem Atalanta's Race in the Earthly Paradise.

Oral History

From the earliest times, people have told stories about the past. Often lacking a written language, they have passed these stories from generation to generation. We call such tales "oral history" or the "oral tradition."

Some of the best examples of oral history come from Africa. Africans developed writing long after the Europeans did, and therefore their histories were kept alive by word of mouth. Every village had an old man called a "griot" who memorized long narratives about the local tribes and families. The "griot" trained younger men, who listened to the oral histories until they knew them well enough to become "griots" themselves. This required remarkable feats of memory. Sometimes the training took as much as 40 years.

Some of the best examples of oral history come from Africa. Africans developed writing long after the Europeans did, and therefore their histories were kept alive by word of mouth. Every village had an old man called a "griot" who memorized long narratives about the local tribes and families. The "griot" trained younger men, who listened to the oral histories until they knew them well enough to become "griots" themselves. This required remarkable feats of memory. Sometimes the training took as much as 40 years.

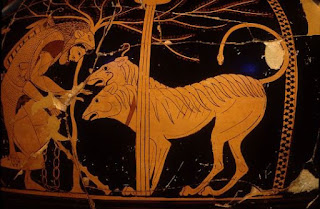

Cerberus, the Three-headed dog

Cerberus, in the mythology of the ancients, the watch dog of the infernal regions. He is represented generally with three heads, the central one more or less human in appearance, with the tail of a serpent and with serpents coiled around his fore legs, body, and neck.

Hercules and Cerberus

What is a Gnome?

Gnome (folklore)

Gnome (folklore)A Gnome is an imaginary being of medieval folklore, usually represented as a bearded, misshapen dwarf. The gnomes are first mentioned by early writers on alchemy, who describe them as an order of subterranean beings supposed to guard treasures and mines. The kobold of German folklore and the unseen knocker who was supposed to haunt English mines are counterparts of the gnome.

Malthus on population

In 1798 an English minister named Thomas R. Malthus wrote An Essay on the Principie of Population As It Affects the Future Improvement of Society. In this essay Malthus said that population was increasing so quickly that the food supply of the world would run out. He urged people, especially the poor, not to marry and have children at a young age.

Malthus believed that overpopulation caused poverty. His theory was much debated during the 1800's. People who disagreed with him said that high birthrates were the result, not the cause, of poverty. Debates about the reasons for population growth and its effects continue today.

Malthus believed that overpopulation caused poverty. His theory was much debated during the 1800's. People who disagreed with him said that high birthrates were the result, not the cause, of poverty. Debates about the reasons for population growth and its effects continue today.

Suicide

Suicide, in law, felo de se, the intentional taking of one's own life. Among uncivilized peoples suicide is by no means unknown, though generally regarded as uncommon. It is favored by the teaching of some Oriental religions, but expressly forbidden by the Koran. Aristotle condemned suicide as unmanly. The Romans, also affected by Stoic doctrine, recognized many legitimate reasons for suicide and punished with confiscation of property only suicides committed to escape punishment for a grave crime. To St. Augustine suicide was essentially a sin, and several church councils, from the 5th century, deprived the corpse of the ordinary rites of the church.

Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac

Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac, 1620-1698, suceeded Courcelles as governor-general of New France in 1672, holding the office until 1682, and again from 1689 to 1698. During his first administration he displayed great ability in dealing with the Indians and in his encouragement of the French explorers, Jolliet, Marquette, and La Salle, who, with Frontenac's assistance, established posts at Mackinac, Niagara, and in the Illinois country. When he returned to Canada in 1689 he found the country almost ruined by the Iroquois tribe of Indians, against whom he at once began a relentless war, but whom he did not succeed in entirely subduing until his final campaign in the Mohawk country in 1696. During this time he also persecuted their allies, the English, ravaging the coast towns of New England and to the south as far as New Jersey. He also captured Salmon Falls, and Schenectady, and in 1690 repulsed the forces of Sir William Phips before Quebec.

Exposition Universelle de Paris 1889

In 1889 the French held a spectacular exposition in Paris to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the French Revolution. In its many buildings it featured examples of the tremendous industrial progress that had been made during the century. To celebrate the exposition, the French newspaper Le Figaro published a special supplement using this poster as its cover. In the foreground is the Seine River with the Eiffel Tower soaring behind. At the time the tower was the tallest structure in the world.

This was the first exposition where electricity was used in a major way, and at night the lower part of the tower and surrounding fountains were lit up, creating a spectacular show. Thousands of examples of advanced machinery, military aircraft, glass, and applied arts were exhibited. In the Gallery of Machines, under the arch of the tower, visitors stood on a high moving platform to view the wonderful inventions that had been developed during the Industrial Revolution. The exposition demonstrated to the world that the 1800's had indeed been technically dynamic.

Exposition Universelle de Paris 1889

The Styx river

|

| The Styx by Doré |

The Centaurs

Centaurs, in Greek mythology, rude, savage monsters, half man and half horse. They were reputed to be descendants of Ixion and a Cloud. It is quite possible that the myth may have been derived from a race of gigantic men inhabiting the mountains and forests of Thessaly. Their chief occupation, it is supposed, was that of hunting. Being horsemen, their raids and quarrels with neighboring tribes were conducted on horseback. This may have given rise to the myth current in Pindar's time of savage hairy beings, half horse and half man. In support of this theory, it may be said that the Aztecs of Mexico were much astonished by the appearance of Cortez's cavalry. Until they saw the men dismount, they thought that horse and rider constituted a two-headed animal. The Centaurs were admitted to social intercourse by the Greeks. At one time they were invited to a marriage, but, becoming intoxicated, they were rude to the bride, and a pitched battle followed. The conflict between the Centaurs and the Greeks is a favorite subject with sculptors and poets of antiquity. Chiron was the most noted of the Centaurs. He was instructed by Apollo and Diana in the mysteries of medicine and music and in the art of prophecy. The Centaurs are represented in art as having the body and legs of a horse. The neck and head of the horse are replaced by the body of a man from the waist upward.

The Battle of the Lapithes and the Centaurs

Who was Sully Prudhomme?

SULLY PRUDHOMME. Rene Francois Armand (1839-1907), was a French poet, born in Paris. In 1865 he published his first volume of poems, Stances et Poemes. Among his later volumes are Impressions de la Guerre, Les Destins, Les Vaines Tendresses, La France, and La Révolte des Fleurs. His poems "La Justíce" and "Le Bonheur" are considered masterpieces of analytic subtlety.

Sully Prudhomme

Marriage Customs

From the earliest times, men and women have contracted marriages and created families in which children could be protected and nurtured. Through the ages there have been many different reasons for forming marriages, and many different ways of deciding who should marry whom. During most periods of history, parents decided who should marry whom, and when.

In medieval times a marriage was looked upon as a way of joining two families together—for economic advantage, for example. Among royal families, in particular, marriages were frequently arranged for political reasons. Marriages could be arranged in childhood, infancy, and sometimes even before birth.

In many cultures marriage was accompanied by an exchange of money or gifts. Because many societies regarded the man as superior the woman's family had to provide a gift or money, known as a dowry to have the daughter married. In other cultures, the husband's family gave money to the bride's family.

The social and economic changes of the Industrial Revolution had numerous effects on the institution of marriage. As the Industrial Revolution spread, young people could earn a living in the new factories. Greater independence made it easier for young people themselves to decide whom to marry and not have to depend on their parents' choice.

The marriage ceremony itself taken many different forms. Perhaps, most familiar to Westerners is the traditional ceremony with the bride in white gown and the groom in formal clothes.

Many wedding traditions symbolize the union between the two partners In ancient China the bridal couple drank from cups that were made from two halves of the same melon. At Japanese weddings, the couple drink wine together, exchanging cups nine times.

In medieval times a marriage was looked upon as a way of joining two families together—for economic advantage, for example. Among royal families, in particular, marriages were frequently arranged for political reasons. Marriages could be arranged in childhood, infancy, and sometimes even before birth.

In many cultures marriage was accompanied by an exchange of money or gifts. Because many societies regarded the man as superior the woman's family had to provide a gift or money, known as a dowry to have the daughter married. In other cultures, the husband's family gave money to the bride's family.

The social and economic changes of the Industrial Revolution had numerous effects on the institution of marriage. As the Industrial Revolution spread, young people could earn a living in the new factories. Greater independence made it easier for young people themselves to decide whom to marry and not have to depend on their parents' choice.

The marriage ceremony itself taken many different forms. Perhaps, most familiar to Westerners is the traditional ceremony with the bride in white gown and the groom in formal clothes.

Many wedding traditions symbolize the union between the two partners In ancient China the bridal couple drank from cups that were made from two halves of the same melon. At Japanese weddings, the couple drink wine together, exchanging cups nine times.

Hugo Grotius

Hugo Grotius, or Huig van Groot, 1583-1645, was a Dutch jurist, famous as the "father" of international law. He was born in Delft and was educated at the University of Leyden. As a child prodigy he became an advocate at the age of 15; by the time he was 21 he had written and edited a number of brilliant works and had already attained considerable recognition in his field of law. In 1613 he went to England with a delegation to attempt to mediate the disputes which led to the later conflicts between the two nations. Being essentially a mediator, Grotius later attempted to conciliate the two religious parties in his native land; he advocated a policy of mutual tolerance. After the victory of the orthodox party Grotius was sentenced to life imprisonment, and his property was ordered confiscated. Escaping by a ruse devised by his wife, he lived for years in Paris; he returned home in 1631 but was quickly expelled, after which time he served for years as the Swedish ambassador to France.

Hugo Grotius, or Huig van Groot, 1583-1645, was a Dutch jurist, famous as the "father" of international law. He was born in Delft and was educated at the University of Leyden. As a child prodigy he became an advocate at the age of 15; by the time he was 21 he had written and edited a number of brilliant works and had already attained considerable recognition in his field of law. In 1613 he went to England with a delegation to attempt to mediate the disputes which led to the later conflicts between the two nations. Being essentially a mediator, Grotius later attempted to conciliate the two religious parties in his native land; he advocated a policy of mutual tolerance. After the victory of the orthodox party Grotius was sentenced to life imprisonment, and his property was ordered confiscated. Escaping by a ruse devised by his wife, he lived for years in Paris; he returned home in 1631 but was quickly expelled, after which time he served for years as the Swedish ambassador to France.Calypso (mythology)

|

| Calypso and Ulysses |

Harriet Hosmer

|

| Harriet Hosmer |

In 1852 Miss Hosmer studied in Rome under John Gibson, the English sculptor. Her most important works are Puck; Oenone, a life sized figure; ideal heads of Daphne and Medusa; statues of Beatrice Cenci, Zenobia, Lincoln, and Benton; the Sleeping Faun and the Waking Faun.

Beatrice Cenci by H. Hosmer

What are Growing pains?

The term "growing pains" is usually applied to the vague and inconstant pains that children sometimes have in their arms or legs. Usually these pains do not seem to have any serious significance and are merely caused by the fact that the child is growing so fast that his bones and muscles have not kept their proper relations to each other. In mild cases plenty of sunshine, good food, and the passage of time will usually overcome the difficulty. In a few cases serious structural abnormalities of the spine, joints, or muscles may be present and an orthopedic surgeon should be consulted as to whether braces or other special measures are desirable. Some children with these vague pains seem to have something wrong with one or more of their endocrine glands. Sometimes the pains may disappear after diseased tonsils or adenoids are removed or infected sinuses treated. There is a question whether "growing pains" are in some instances a mild manifestation of rheumatic fever. A child with "growing pains" may develop heart trouble similar to that seen after rheumatic fever, and this suggests a possible relationship in a few instances though this seems to be the exception.

Geranium (plant)

Geranium is any of large group of plants widely cultivated for their decorative flowers and attractive and fragrant leaves. Geraniums are native to moist shady areas throughout temperate and subtropical regions. They usually range in height from 1 to 2 feet, but some species are only a few inches high, and others may reach a height of 6 feet. The flowers always consist of five petals, and they usually range from white to pink, purple, and deep red. The leaves of the geranium are usually lobed and are covered with many fine hairs.

Cultivated geraniums are usually divided into four categories, according to their use. Fancy, or show, geraniums are cultivated for their large showy clusters of flowers and are often planted indoors in pots. Zonal geraniums are raised in window boxes or gardens for their leaves, which may be bronze or gold and are sometimes edged with white. Ivy-leaved geraniums have weak trailing stems and are often grown in hanging baskets. Scented-leaved geraniums are grown for their fragrant leaves, and some, such as the rose geranium (Pelargonium odoratissimum), yield an oil that is used in the manufacture of perfume and soap.

Cultivated geraniums are usually divided into four categories, according to their use. Fancy, or show, geraniums are cultivated for their large showy clusters of flowers and are often planted indoors in pots. Zonal geraniums are raised in window boxes or gardens for their leaves, which may be bronze or gold and are sometimes edged with white. Ivy-leaved geraniums have weak trailing stems and are often grown in hanging baskets. Scented-leaved geraniums are grown for their fragrant leaves, and some, such as the rose geranium (Pelargonium odoratissimum), yield an oil that is used in the manufacture of perfume and soap.

What are warts?

Wart, known in surgery by the Latin name Verrucae, is a collection of lengthened papillae of the skin, closely adherent and ensheathed by a thick covering of hard dry cuticle. From friction and exposure to the air the surface presents a horny texture, and is rounded off into a small button-like shape. Such is the description of the simple wart, which is so commonly seen on the hands and fingers (and rarely on the face or elsewhere) of persons of all ages, but especially of children. Among other varieties of warts are: 1) Sublingual warts, growing, as their specific name implies be-neath or at the side of the finger or toe nails. They originate beneath the nail, and as they increase they crop out either at the free extremity or the side of the nail, and are usually troublesome and often very painful. 2) Venereal warts, caused by the direct irritation of the discharges of gonorrhea or syphilis, and occurring about the parts which are liable to be polluted with such discharges. They attain a larger size, and are more fleshy and vascular than other warts.

Théodore Géricault

Théodore Géricault was a noted French painter. Born Jean Louis André Théodore Géricault, at Rouen, France, Sept. 26, 1791. Died Paris, France, Jan. 26, 1824.

Géricault was a forerunner of the Romantic movement in art. He was the first major artist to rebel against the idealistic Neoclassical tradition by choosing for his subjects events from contemporary life. Typical of his dramatic style are his studies of riders and horses in motion, his portraits of the insane, and his vivid pictures of important current events. His best-known single work is the Raft of the Medusa (the Louvre, Paris), a violent portrayal of the survivors of a notorious shipwreck. The painting caused a public sensation at the 1819 Salon.

Brought up in Paris, Géricault studied art with Carie Vernet and Fierre Guérin. His early paintings of military scenes and horses shocked the Academy of Fine Arts with their spontaneity and emphasis on violence. Even more revolutionary were his antislavery subjects and other works in behalf of freedom and social reform.

Géricault's early death was the result of an accident while horseback riding. Although his active career lasted for only 12 years and he exhibited only three paintings, Géricault greatly influenced the works of Delacroix, Courbet, and other important artists of the 19th century.

|

| Raft of the Medusa |

Brought up in Paris, Géricault studied art with Carie Vernet and Fierre Guérin. His early paintings of military scenes and horses shocked the Academy of Fine Arts with their spontaneity and emphasis on violence. Even more revolutionary were his antislavery subjects and other works in behalf of freedom and social reform.

Géricault's early death was the result of an accident while horseback riding. Although his active career lasted for only 12 years and he exhibited only three paintings, Géricault greatly influenced the works of Delacroix, Courbet, and other important artists of the 19th century.

Robert Moses Grove

|

| Lefty Grove |

What is a Hotbed?

The Hotbed is a frame in which to hasten the early growth of plants. The foundation of the common hotbed is a pit filled with a fermenting, heat-giving substance. Horse manure is considered excellent. The amount should vary with the locality. A depth of eighteen inches is regarded as sufficient for zero weather. This may be covered with a layer of earth in which seeds or slips are planted. The whole is protected with a frame and covered with glass. The top of the frame should slope to the south to catch the rays of the sun. The sash cover should be hinged so that it may be raised for ventilation during the heat of the day. The sash may be covered by matting during cold nights. Hotbeds are less expensive than greenhouses. They are relied on to bring forward young plants of lettuce, cabbage, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, cucumbers, and the like, so as to have them ready for transplanting in the open air when warm weather comes.

Wartburg Castle

Wartburg Castle is a notable structure near Eisenach, Saxe-Weimar, on an eminence rising 600 feet above the town, engirt by forests, founded in 1067, and till 1440 the residence of the Landgrave of Thuringia. It is famous as the spot where the Minnesingers assembled, probably in 1207, to hold their famed poetic contest known as the Sangerkrieg or " battle of song." Among the renowned minstrels who participated, according to the unknown author of a poem written abont 1290 which described the contest, were Wolfram von Eschenbach, Heinrich von Ofterdingen. and Walther von der Vogelweide. This incident is celebrated in Wagner's Tannhauser. The Wartburg was also known as the home of St. Elizabeth (1207-1231); and as the 10 months' asylum to which Luther was carried by the Elector of Saxony (May, 1521). The chapel in which Luther preached, as well as the chamber which he occupied. and in which he discomfited the Evil One by throwing the inkstand at his head. is still pointed out. The whole pile has been magnificently restored since 1851.

Did you know that...

Did you know that...

not all cell types use the same amount of energy?

The human body is made up of billions of cells. All cells need energy to carry out their basic activities. This energy comes from breaking the chemical bonds of the molecules in the foods we eat. But because cells are specialized for specific tasks, they each need different amounts of energy each day. For example, in an adult the brain makes up only about 2 percent of the body's total weíght, but it uses about 20 percent of the body's total energy when the body is at rest. Much of this energy is used for powering the nerve impulses in its many brain cells. The liver also uses about 20 percent of the body's total energy. The heart uses about 10 percent of the body's energy and the skeletal muscles use about 20 percent of the body's energy when at rest, but the amount of energy required for the cells in these organs rises significantly when the body is physically active.

not all cell types use the same amount of energy?

The human body is made up of billions of cells. All cells need energy to carry out their basic activities. This energy comes from breaking the chemical bonds of the molecules in the foods we eat. But because cells are specialized for specific tasks, they each need different amounts of energy each day. For example, in an adult the brain makes up only about 2 percent of the body's total weíght, but it uses about 20 percent of the body's total energy when the body is at rest. Much of this energy is used for powering the nerve impulses in its many brain cells. The liver also uses about 20 percent of the body's total energy. The heart uses about 10 percent of the body's energy and the skeletal muscles use about 20 percent of the body's energy when at rest, but the amount of energy required for the cells in these organs rises significantly when the body is physically active.

Who was Julius Rosenwald?

Julius Rosenwald (1862-1932), was an American businessman and philanthropist. He contributed about $63 million to Black education, Jewish philanthropies, and a wide range of educational, religious, scientific, and community organizations and institutions. Rosenwald established the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago.

He once said it was easier to make $1 million honestly than to give it away wisely. He tried to aid groups rather than individuals and to make his gifts in such a way as to stimulate contributions from others. He donated money through the Julius Rosenwald Fund and other separate donations. He disliked perpetual endowments, and ordered that all of the Julius Rosenwald Fund be spent within 25 years of his death.

Rosenwald was born and educated in Springfield, Illinois. He entered the clothing business at age 17, and joined Sears, Roebuck and Company in 1895. He was president of Sears from 1909 to 1924.

He once said it was easier to make $1 million honestly than to give it away wisely. He tried to aid groups rather than individuals and to make his gifts in such a way as to stimulate contributions from others. He donated money through the Julius Rosenwald Fund and other separate donations. He disliked perpetual endowments, and ordered that all of the Julius Rosenwald Fund be spent within 25 years of his death.

Rosenwald was born and educated in Springfield, Illinois. He entered the clothing business at age 17, and joined Sears, Roebuck and Company in 1895. He was president of Sears from 1909 to 1924.

What are the Horse Latitudes?

Horse Latitudes are a portion of the Atlantic Ocean which is near the Tropic of Cancer, and which is noted for the long duration of its calms. The name is also given to a region along the polar edge of the trade-wind belts.

The name arose, so the story goes, from the fact that ships sailing from New England to the West Indies freighted with loads of horses, through the long detention through calms in this region, had to throw the horses overboard, because they had died from lack of water.

The name arose, so the story goes, from the fact that ships sailing from New England to the West Indies freighted with loads of horses, through the long detention through calms in this region, had to throw the horses overboard, because they had died from lack of water.

Why is a tree or an American flag sometimes placed on the highest part of a building under construction?

A tree or flag placed on, or nailed to, the highest part of a building under construction is a modern version of the ancient "topping out" ceremony. Topping out, still practiced in many parts of the world, is meant to indícate that the frame of the structure has been completed. During a topping out ceremony of long ago, a barrel of beer might be drunk while a tree or wreath was attached to the ridge of a building's newly completed roof. Today, finishing the frame of a building is still cause for celebration.

Thomas Warton (the younger)

Thomas Warton was an English poet and critic, son of the Rev. Thomas Warton (the elder), professor of poetry at Oxford; born in Basingstoke, England, in 1728. He was educated at Winchester, and Oxford, and early distinguished himself by his poetical compositions and criticisms. Warton was chosen professor of poetry at Oxford in 1757, a chair he filled with great ability for 10 years; appointed Camden professor of history in 1785; and he succeeded Whitehead as poet laureate in the same year. Several church livings were also held by him. He rendered great service to literature by his History of English Poetry (1774-1781, three vols.), a work never completed. He became known as a critic by his Observations on the Fairie Queen (1754-1762). His last considerable work was Poema upon Several Occasions by John, Milton. Thomas Warton died in Oxford, May 21, 1790. His brother, Joseph. was also a critic.

What is grounding?

Electrical grounding, or earthing, is a common return, a completion of the circuit, for many electrical circuits. The earth can be used as this common return path, hence the term grounding. Often the metal frame-work on which electrical apparatus is mounted, or a heavy conductor, may be called a ground, although actual contact with the earth may not be made. In telegraph and telephone circuits the earth may be used as a common return for all or part of the circuits. Radio transmitters and receivers may also make use of the return effect of the earth's conductivity or capacity.

As a safety feature, electrical power lines usually have one wire connected with the earth; this connection is usually carried through to the outermost electrical connection on all light fixtures. Accidental contact with a light fixture properly connected in this way will do little harm. (Since all plumbing is grounded, one should carefully avoid touching any plumbing or water flowing from the plumbing while contacting any electrical fixture.) Electrical machines usually have their frames grounded by a special ground wire that may be provided in the cable leading to them. Household washing machines, ironers, and electric stoves, may be so protected.

Electric street cars, elevated trains, and electric trains often use the rails as a return ground connection. Vehicles such as automobiles, airplanes, and boats usually have one side of electrical circuits connected to the metal framework, and thus this framework may become the common return path for many circuits.

As a safety feature, electrical power lines usually have one wire connected with the earth; this connection is usually carried through to the outermost electrical connection on all light fixtures. Accidental contact with a light fixture properly connected in this way will do little harm. (Since all plumbing is grounded, one should carefully avoid touching any plumbing or water flowing from the plumbing while contacting any electrical fixture.) Electrical machines usually have their frames grounded by a special ground wire that may be provided in the cable leading to them. Household washing machines, ironers, and electric stoves, may be so protected.

Electric street cars, elevated trains, and electric trains often use the rails as a return ground connection. Vehicles such as automobiles, airplanes, and boats usually have one side of electrical circuits connected to the metal framework, and thus this framework may become the common return path for many circuits.

Horse racing in the ancient world

The practice of horse racing is of great antiquity. The Persians were familiar with the saddle. The Numidians rode madly without halter or bridle. The horse and his rider were well known to the Egyptians. Chariot races were held on the plains of Troy. King Solomon bought riding horses in Egypt, paying a small fortune for apiece. Horses were introduced into the Greek games as early as 648 B. C. The horse race was a regular part of the entertainment offered by the Roman circus. In Ben Hur, General Wallace gives a spirited account of a race according to the rules of a Roman circus.

The Washington Monument

The Washington Monument is a majestic monument erected in honor of George Washington. It stands in the Mall on the banks of the Potomac, Washington, D. C. The corner stone was laid by President Polk, July 4, 1848, and Dec. 6, 1884, the cap stone was set in position. The foundations are 126½ feet square and 36 feet 8 inches deep. The base of the monument is 55 feet 1½ inches square and the walls 15 feet thick. At the 500 foot mark, where the pyramidal top begins, the shaft is 34 feet 5½ inches square and the walls are 18 inches thick. The monument is made of blocks of marble two feet thick, and its height above the ground is 555 feet. The pyramidal top terminates in an aluminum tip, which is 9 inches high and weighs 100 ounces. The total weight, foundation and all, is nearly 81,000 tons. An immense iron framework supports the machinery of the elevator. At one side begin the stairs, of which there are 50 flights, containing 18 steps each. Five hundred and twenty feet from the base there are eight Windows, two on each face. The Washington monument is the highest masonry monument in the world; total cost. $1,500,000.

What is rosewood?

Rosewood is the name of several kinds of attractive wood of the botanical genus Dalbergia. It is used either as solid wood or as veneer in making ornamental furniture and musical instruments. Its ability to take a high polish and its rich color make rosewood valuable. Its color runs from dark reddish-brown to purplish-brown. Its name comes from the roselike odor of the wood when it is sawed. It is sometimes called blackwood. Rosewood grows in Brazil, Central America, Southern Asia. and Madagascar.

Scientific Classification. Rosewoods are in the pea family, Leguminosae. They are genus Dalbergia.

Scientific Classification. Rosewoods are in the pea family, Leguminosae. They are genus Dalbergia.

Rosewood

First Hospitals

Hospitals appear to have been unknown among the ancients. Little provision, if any, was made for the care even of the wounded on the field of battle. The Greek and Roman armies had no medical staff. The monasteries set apart a room for the sick. The modern hospital is an outgrowth of this custom. At the time of the English Reformation the monks were in charge of the hospital service of the kingdom. This branch of the monastery was retained in several instances and grew into a large establishment. It became, we may say, fashionable for wealthy men to endow hospitals. In England a common term for both dispensaries and hospitals is "infirmary."

The ancient Greeks are said to have been treated by Aesculapius at Epidaurus. The early Jews had houses for healing, one of them being Beth Saida, spoken of in the New Testament. The growth of Christianity gave a great Impetus to all forms of charity, and from the service of the monks in caring for the sick slowly grew the present admirable system of hospital work.

The ancient Greeks are said to have been treated by Aesculapius at Epidaurus. The early Jews had houses for healing, one of them being Beth Saida, spoken of in the New Testament. The growth of Christianity gave a great Impetus to all forms of charity, and from the service of the monks in caring for the sick slowly grew the present admirable system of hospital work.

The first hospitals in Europe were established in the Middle Ages

Why don't tall buildings blow down in a strong wind?

Tall buildings must be braced throughout their height with cross-bracing, rigid connections, or stiff structural walls called shear walls. Most tall buildings are constructed of steel or reinforced concrete. These materials are flexible—that is, they can bend slightly without breaking. When strong winds blow, the steel and concrete buildings give way to the force of the wind by bending a little. For example, the Sears Tower in Chicago was designed to sway as much as 10 inches (25 centimeters). If tall buildings did not sway, they could be snapped in two by violent wind. The buildings are not pulled out of the ground because they are firmly anchored in strong foundations.

Cartography

Whenever a place, a direction, or a route cannot be described clearly in words, people resort to drawings. Historians can learn a great deal about a society from the way it chooses to produce such drawings, which we usually call maps.

The oldest surviving maps are clay tablets and papyrus remnants from Babylonia and Egypt. Called cadastres, they are sketches of property lines, showing where one person's property ended and another's began. The survival of these maps from 4,000 or more years ago indicates how important it was in ancient societies to define exactly the property that a person held.

The oldest surviving maps are clay tablets and papyrus remnants from Babylonia and Egypt. Called cadastres, they are sketches of property lines, showing where one person's property ended and another's began. The survival of these maps from 4,000 or more years ago indicates how important it was in ancient societies to define exactly the property that a person held.

What was The Protestant Reformation?

The Protestant Reformation changed religious attitudes

Around 1500 a number of northern humanists were suggesting that the Church had lost sight of the spiritual mission proclaimed by Jesus himself. Instead of setting an example of moral leadership, they said, popes were becoming political leaders and warriors. Instead of encouraging inner piety, priests were concerned about the details of ceremonies. And the Church as a whole, they said, seemed more interested in its income than in salvation. What the northern humanists were seeking was a new emphasis on personal faith and spirituality. When their message went unheard in the Church, a new generation of reformers urged believers who were unhappy with official religion to join a new church. This religious revolution, which split the Church in Western Europe, is called the Reformation.

George Herbert

|

| George Herbert (1593-1633) |

Herbert was born into a noble Welsh family. Ordained about 1626, he gave up a career at court and at Cambridge University to become a devoted parish priest, from 1630 to his death.

Jean Antoine Houdon

Jean Antoine Houdon (1740-1828) was the greatest French sculptor of his day, was born at Versailles. He began work in his art at a very early age, and at twenty won the coveted Prix de Rome. Houdon studied in Rome for ten years, at the end of which he returned to Paris as instructor at the School of Fine Arts. Among his finest works are the busts of Catherine II, Moliere, Rousseau, Voltaire, Buffon, Lafayette, Napoleon, Franklin and Washington. To make the latter, which is now in the state capitol of Richmond, Va., Houdon accompanied Franklin to the United States in 1785. It is considered the finest likeness of Washington extant.

Bust of Washington (Houdon)

Did you know that...

Did you know that...

as many as 250,000 new nerve cells can be formed each minute during a baby's development inside its mother? By the time the baby is born, the brain will have almost all the nerve cells, or neurons, it will ever nave. However, a child's brain continúes to increase in size after birth as other brain cells, called glia, grow around the neurons, insulating them and carrying out various "housekeeping" functions in the brain. A baby is also born with trillions of connections, or synapses, be-tween neurons. As the child learns various skills, many of these synapses are stimulated and become permanent connections.

Christopher Columbus

Even before Vasco da Gama brought wealth to Portugal, Spain also had become interested in the search for new trade routes. Its rulers, Ferdinand and Isabella, decided to finance a voyage by Christopher Columbus, an Italian navigator. Thinking that the world was much smaller than it actually is, Columbus believed he could reach India quickly and easily by sailing westward.

In August 1492 Columbus set sail with three small ships from Spain and crossed the Atlantic. His small fleet landed in October on a tiny island in the Caribbean Sea. He named the island San Salvador. After visiting several other islands, Columbus returned triumphantly to Spain in the spring of 1493 to report his discoveries. He believed the islands to be off the coast of India and therefore called their inhabitants "Indians." Actually, he had discovered the islands later known as the West Indies. Although Columbus made three more voyages between 1493 and 1504, he believed until his death that the lands he had found were part of Asia.

In August 1492 Columbus set sail with three small ships from Spain and crossed the Atlantic. His small fleet landed in October on a tiny island in the Caribbean Sea. He named the island San Salvador. After visiting several other islands, Columbus returned triumphantly to Spain in the spring of 1493 to report his discoveries. He believed the islands to be off the coast of India and therefore called their inhabitants "Indians." Actually, he had discovered the islands later known as the West Indies. Although Columbus made three more voyages between 1493 and 1504, he believed until his death that the lands he had found were part of Asia.

Romance languages

A Romance language is any of several languages that developed from Latin. The Romance tongues include French, Italian, Spanish, Catalan, Portuguese, and Romanian. Other Romance, or Romanic, languages are Sardinian and Rhaeto-Romance (the general name for a group of languages, including Romansh, spoken in certain parts of Switzerland, the Tyrol, and Friuli).

The Romance group also includes Provençal, the language spoken in southern France. Provençal was the language of the troubadours, who were the poets of the 1100's. The lyrics of more than 400 Provençal poets have come down to us. Most of their poems were love lyrics, but some had moral, religious, or political themes written to popular melodies. The use of Provençal as a literary medium began to decline soon after A. D. 1200.

Romance languages grew up because Rome sent colonists to settle the countries it had conquered. The soldiers, tradesmen, and farmers who colonized these conquered countries took their language with them, but it was not the Latin of the classics studied in school today. It was popular, or vulgar, Latin, the everyday speech of ordinary people. This popular Latin often adopted words or features of pronunciation from the language of the conquered country. For example, the Latin word for hundred, centum, became cent in French, ciento in Spanish, and cento in Italian. The varieties of popular Latin formed in this way eventually developed into separate languages.

The Romance group also includes Provençal, the language spoken in southern France. Provençal was the language of the troubadours, who were the poets of the 1100's. The lyrics of more than 400 Provençal poets have come down to us. Most of their poems were love lyrics, but some had moral, religious, or political themes written to popular melodies. The use of Provençal as a literary medium began to decline soon after A. D. 1200.

Romance languages grew up because Rome sent colonists to settle the countries it had conquered. The soldiers, tradesmen, and farmers who colonized these conquered countries took their language with them, but it was not the Latin of the classics studied in school today. It was popular, or vulgar, Latin, the everyday speech of ordinary people. This popular Latin often adopted words or features of pronunciation from the language of the conquered country. For example, the Latin word for hundred, centum, became cent in French, ciento in Spanish, and cento in Italian. The varieties of popular Latin formed in this way eventually developed into separate languages.

Why were some of the early bridges in the United States covered?

Covered bridges once dotted the American countryside from the Atlantic Coast to the Ohio River. The bridges looked like square tunnels with peaked roofs. Some people claim that the bridges were covered so that horses would not be frightened by the water underneath. Others say that they were built as a shelter for travelers in faad weather. Actually the coverings were designed to protect the wooden framework and fiooring of the bridges and keep them from rotting. The pitched roofs, which shed snow, also reduced the amount of heavy snow that collected on the bridges. Wooden bridges became obsolete as traffic loads increased and modern trucks grew in size. Today only a few are still stand-ing. Many people work to preserve the remaining covered bridges.

Realism and Perspective in Giotto's art

The changes in painting from medieval to modern times can be seen in the work of the great early Renaissance artist Giotto. In this painting the angel of God tells St. Anne that she will have a child, Mary, who will be the mother of Jesus. There is a three-dimensional quality in the lighted room, in the rooftops that recede into the dark, and in the faces of the women and the angel. Thus Giotto makes us feel the scene is an actual event rather than a symbolic one.

Giotto was an architect as well as an artist. His interest in architectural detail and perspective heighten the realism of his work. Like other Renaissance artists, he was interested in showing a building or a landscape as it appeared through a person's own eyes. Later Renaissance painters developed perspective mathematically and were able to portray distances with great accuracy.

Giotto was an architect as well as an artist. His interest in architectural detail and perspective heighten the realism of his work. Like other Renaissance artists, he was interested in showing a building or a landscape as it appeared through a person's own eyes. Later Renaissance painters developed perspective mathematically and were able to portray distances with great accuracy.

What is Horsepower?

Horsepower is literally the power of a horse or the rate at which it can perform work. With the invention of the steam-engine, it became necessary for Watt to express its power in terms of the horse, and the standard he established has been generally adopted. So the horsepower became equivalent to the raising of thirty-three thousand pounds one foot high in one minute, or to the doing of work at the rate of thirty-three thousand foot pounds per minute. This somewhat exceeds the activity of an average horse except for limited periods. The determination of the horsepower of a steam-engine is a comparatively simple matter. Multiply together the area of the piston in square inches, the length of the stroke in feet, the mean effective pressure of the steam in pounds per square inch, and the number of strokes per minute, and divide the product by thirty-three thousand. It is customary to subtract ten percent for friction.

The unit of power in metric units is the watt, named from the inventor, and is equal to doing work at the rate of one joule, or ten million ergs, per second. The kilowatt is of more practical size, and equals one and one-third horsepower.

The unit of power in metric units is the watt, named from the inventor, and is equal to doing work at the rate of one joule, or ten million ergs, per second. The kilowatt is of more practical size, and equals one and one-third horsepower.

Is it true that we use only 10 percent of our brains?

No. This is a common misconception. Although different parts of the brain are more or less active during different activities, there is no evidence that we use only a small portion of our brains. Damage to a small area of the brain can cause devastating effects, such as amnesia, paralysis, or loss of language. This suggests that every part of the brain serves an important function, upon which other parts of the brain depend.

On the other hand, some people— especially children—can recover after suffering major damage to the brain or even losing part of it. Such remarkable recoveries do not suggest that we need only a fraction of our brain, however. Rather, they illustrate the tremendous capacity of the brain to "rewire" itself: Cells in the remaining parts of the brain form new connections and take over the functions of those parts that were removed.

On the other hand, some people— especially children—can recover after suffering major damage to the brain or even losing part of it. Such remarkable recoveries do not suggest that we need only a fraction of our brain, however. Rather, they illustrate the tremendous capacity of the brain to "rewire" itself: Cells in the remaining parts of the brain form new connections and take over the functions of those parts that were removed.

Frederick the Great

Frederick William I had a real worry as he nearer the end of his life. His son had little interest in either military life or government service. Instead, he spent his time writing poetry, playing the flute, and reading philosophy. The king used the harshest methods, even imprisonment to force his heir to be more nearly the son he desired.

As it turned out, Frederick William's son proved to be an even stronger ruler than his father. He turned out to be one of Prussia's greatest military and political leaders and is known Frederick the Great.

Frederick William's son took the throne of Prussia as Frederick II in 1740, the same year in which Maria Theresa became ruler of Austria. He was a skilled administrator, who instituted social reforms and began work on a Prussian law code. Like his grandfather, he admired French culture He also wrote several books, including a history of Brandenburg and a book on the duties of rulers.

As it turned out, Frederick William's son proved to be an even stronger ruler than his father. He turned out to be one of Prussia's greatest military and political leaders and is known Frederick the Great.

Frederick William's son took the throne of Prussia as Frederick II in 1740, the same year in which Maria Theresa became ruler of Austria. He was a skilled administrator, who instituted social reforms and began work on a Prussian law code. Like his grandfather, he admired French culture He also wrote several books, including a history of Brandenburg and a book on the duties of rulers.

Victor Herbert

Victor Herbert (1859-1924) was an American composer and conductor, is often called "the prince of operetta." One of his most famous operettas is Babes in Toyland (1903), which was based on Mother Goose and fairyland characters. "March of the Toys" and "Toyland" are well-loved numbers in this operetta. He also wrote Mlle. Modiste (1905), which includes the popular song "Kiss Me Again." Naughty Marietta (1910), one of the most tuneful of his operettas, includes such songs as "Ah! Sweet Mystery of Life," "I'm Falling in Love with Someone," "Italian Street Song," and " 'Neath the Southern Moon."

Herbert was born on Feb. 1, 1859, in Dublin, Ireland, of a musical family. He studied the cello in Germany, and played in leading European orchestras. In 1886, he settled in New York City, where he played cello in the Metropolitan Opera Company Orchestra. In 1893, Herbert followed Patrick S. Gilmore as bandmaster of the Twenty-second Regiment Band. He wrote his first operetta, Prince Ananias, in 1894. It was not a great success, but The Wizard of the Nile, a year later, proved a major success.

Herbert was born on Feb. 1, 1859, in Dublin, Ireland, of a musical family. He studied the cello in Germany, and played in leading European orchestras. In 1886, he settled in New York City, where he played cello in the Metropolitan Opera Company Orchestra. In 1893, Herbert followed Patrick S. Gilmore as bandmaster of the Twenty-second Regiment Band. He wrote his first operetta, Prince Ananias, in 1894. It was not a great success, but The Wizard of the Nile, a year later, proved a major success.

Did you know that . . .

Some 650 muscles cover the body's skeleton? Muscles do more than shape and define the contours of our bodies. They are responsible for all of the body's movements. Muscles are attached to bones by tough, hard tissue called tendons. In response to instructions from the brain, muscles contract and pull on the bones and movement occurs. Usually skeletal muscles work in groups. Even aseemingly simple task such as taking one step involves about 200 muscles! Some muscles lift and move your leg forward, while others in the back, chest, and abdomen help keep you from losing your balance during the motion.

Leather

Of all the ancient industries that of the manufacture of leather is one of the most interesting on account of the convertibility of an easily descomposed substance into one which resists putrefaction. The manufacture of leather is as old as history itself. In China the manufacture and use of leather was known before the Christian era, and in Egypt leather has been found in mausoleums of the ancients, showing us that rations in the remote ages of the past were practised in the art and left slight traces of their high civilization to be admired today. The Persians and Babylonians passed the art over the Greeks and Romans and so down through the different medieval nations to us. The American Indians were also well versed in the art of making leather. Although their method of tanning was entirely different from that of the ancient races, the fact remains that they also discovered a way of treating the skins of animals in such a way as to prevent the putrefaction of animal tissues.

Money in history

In early times any object that everyone accepted as valuable could serve as money. The Romans, for example, paid their soldiers with what was then a prized commodity, salt. From this custom we get the phrase, "worth ore's salt." Other items that have been used as money include shells, tobacco, feathers, and whale teeth.

Probably the first money made specifically as a medium of exchange appeared in China during the Shang dynasty. Because farmers often had traded spades and knives for other goods, this ancient money was shaped like spades.

Increasingly, rare metals, especially gold and silver, came to be used as money. They were fashioned into coins, which could be carried easily. Governments jealously guarded the right to make coins and to establish their value. Often, however, government officials would clip pieces off coins. Then they would melt these down to make more coins so that they could buy more. During the 1500's this process brought on inflation and was stopped only when milled, or grooved, edges were put on coins. This enabled people to see at once if the coins had been clipped.

About this time, too, paper money became more common. The Chinese, the first to use both paper and movable type, were also the first to use paper money, about the year 1060 A. D. Paper money was even more convenient than coins and became especially useful as long-distance trade grew increasingly important.

Probably the first money made specifically as a medium of exchange appeared in China during the Shang dynasty. Because farmers often had traded spades and knives for other goods, this ancient money was shaped like spades.

|

| coin |

About this time, too, paper money became more common. The Chinese, the first to use both paper and movable type, were also the first to use paper money, about the year 1060 A. D. Paper money was even more convenient than coins and became especially useful as long-distance trade grew increasingly important.

Who were the Hesperides?

In Greek mythology, the Hesperides were the daughters of Atlas and Hesperus (Evening). They lived at the western end of the world. They guarded the golden apples which Gaea (Earth) gave to Hera when she married Zeus. A sleepless dragon helped them. One of Hercules' labors was to steal these apples.

Hesperides

Iron

Iron is a hard, heavy, well known metal. Pure iron is silvery-white in color, but it is seldom seen. Wrought iron is the purest commercial form; yet piano strings, the purest wrought iron in the market, contain three pounds to the thousand of carbon and other elements. When in the presence of a magnet, or when placed with-in a coil through which an electric current is passing, soft iron becomes magnetic. Iron remains unchanged in dry air, but rusts —unites with oxygen—in moist air.

Iron is the most useful of all metals, and of all metals it is the most widely distributed in nature. It forms a twentieth part of the world's crust. It is essential to life of all sorts. It is found in the green chlorophyll of plants and in the blood of animals. It occurs in meteorites. The color spectrum shows that iron is present in the Sun. There is an iron mountain near Durango, Mexico. It is a projecting back-bone or dike of solid iron ore,—a huge mass one mile long, a third of a mile wide, and 450 to 650 feet high. Similar hills in Missouri are known as Iron Mountain and Pilot Knob.

Iron is the most useful of all metals, and of all metals it is the most widely distributed in nature. It forms a twentieth part of the world's crust. It is essential to life of all sorts. It is found in the green chlorophyll of plants and in the blood of animals. It occurs in meteorites. The color spectrum shows that iron is present in the Sun. There is an iron mountain near Durango, Mexico. It is a projecting back-bone or dike of solid iron ore,—a huge mass one mile long, a third of a mile wide, and 450 to 650 feet high. Similar hills in Missouri are known as Iron Mountain and Pilot Knob.

Iron meteorite

What was the Fries Rebellion?

The Fries Rebellion was an uprising in eastern Pennsylvania in 1799, led by John Fries (1764-1825). By act of July 14, 1798, Congress imposed a direct tax of $2,000,000, which was to be equitably apportioned among the various states and which was laid upon all dwelling houses and lands, and on slaves between the ages of 12 and 50. The value of the dwelling houses was to be determined on the basis of the size and number of Windows in these houses, and an impression thus got abroad that citizens who owned houses were being taxed for having Windows, the tax thus coming to be known in some communities as a "window tax." In the eastern counties of Pennsylvania (Northampton, Bucks, Montgomery, Lehigh and Berks), the large German element vigorously opposed the tax, and under the leadership of Fries, resisted by force (March, 1799) the Federal officers sent to measure Windows preparatory to assessing the owners of dwelling houses.

Riots soon broke out; some 30 of the rioters were arrested; and at Bethlehem these arrested rioters were rescued by their associates led by Fries. President Adams issued a proclamation against the rioters, troops were called out, and the disturbances were quickly suppressed. Fries was arrested, was tried on a charge of treason—the first trial of the sort in the history of the United States—and was convicted (1799). A new trial, however, was granted, but in the following year Fries was again convicted and was sentenced to the gallows. It was partly for the high-handed manner in which Judge Chase conducted this trial that he was impeached by the House and tried before the Senate. Fries was pardoned by President Adams, and subsequently became a prosperous dealer in tinware in the city of Philadelphia.

Who was Theodor Herzl?

Theodor Herzl (1860-1904) was an Austrian journalist and playwright who founded the Zionist movement. The aim of this movement was to set up a Jewish national home in Palestine. Herzl was born in Budapest, Hungary, and studied law at the University of Vienna.

The growing problem of anti-Jewish feeling in Europe, increased by the Dreyfus case in France, attracted Herzl's attention. He saw that European Jews had failed to gain social equality even when they had become politically free. So Herzl got the idea of gathering the scattered Jews into a country and a nation of their own. His motives were economic and social, rather than religious. Herzl's Jewish State, published in 1896, attracted many persons to this cause.

Max Nordau and Israel Zangwill were among them. Herzl kept up contact with the leaders of many nations. In 1897, he presided over the first Zionist congress in Basel, Switzerland. In 1901, Great Britain offered the Jewish people land in British East Africa. Worry about the dispute over this offer injured Herzl's health and hastened his death.

The growing problem of anti-Jewish feeling in Europe, increased by the Dreyfus case in France, attracted Herzl's attention. He saw that European Jews had failed to gain social equality even when they had become politically free. So Herzl got the idea of gathering the scattered Jews into a country and a nation of their own. His motives were economic and social, rather than religious. Herzl's Jewish State, published in 1896, attracted many persons to this cause.

Max Nordau and Israel Zangwill were among them. Herzl kept up contact with the leaders of many nations. In 1897, he presided over the first Zionist congress in Basel, Switzerland. In 1901, Great Britain offered the Jewish people land in British East Africa. Worry about the dispute over this offer injured Herzl's health and hastened his death.

Hesiod (Greek poet)

HESIOD (700's B.C.), was the first major Greek poet after Homer. He was the first poet to write didactic (instructional) poetry, and the first to reveal his personality through his poetry.

His major work, Works and Days, is addressed to his brother Perses. In it, Hesiod speaks of his town of Ascra in Boeotia as being "cold in winter, hot in summer, and pleasant at no time." Instead of glorifying warrior heroes as Homer did, Hesiod advocated hard work, frugality, and prudence. Works and Days includes practical advice on how to live and farm, and specifies dates on which certain tasks ought to be done. It also contains a story of the fall of man through Pandora's untimely curiosity. It describes the deterioration of the world through five stages: the Age of Gold; the Silver Age; the Bronze Age; the Age of Heroes; and the Age of Iron. Hesiod lived in the Age of Iron. Another work believed to be Hesiod's is Theogony. In it, he tried to solve conflicting accounts of the Greek gods and their functions.

His major work, Works and Days, is addressed to his brother Perses. In it, Hesiod speaks of his town of Ascra in Boeotia as being "cold in winter, hot in summer, and pleasant at no time." Instead of glorifying warrior heroes as Homer did, Hesiod advocated hard work, frugality, and prudence. Works and Days includes practical advice on how to live and farm, and specifies dates on which certain tasks ought to be done. It also contains a story of the fall of man through Pandora's untimely curiosity. It describes the deterioration of the world through five stages: the Age of Gold; the Silver Age; the Bronze Age; the Age of Heroes; and the Age of Iron. Hesiod lived in the Age of Iron. Another work believed to be Hesiod's is Theogony. In it, he tried to solve conflicting accounts of the Greek gods and their functions.

What is water gas?

Water Gas is a colorless gas that burns with a hot, blue flame. Water in the form of steam is passed over red-hot coke, forming hydrogen and carbon monoxide. The hydrogen and carbon monoxide are then passed through a retort in which carbonaceous matter such as resin is undergoing decomposition absorbing therefrom sufficient carbon to render it luminous when burned. The average composition of water gas is approximately: carbon monoxide, 40-50 percent; hydrogen, 45-50 percent; carbon dioxide, 3-7 percent; nitrogen, 4-5 percent.

Car improvements

Since the 19th century the automobile it developed quite fast. Between World Wars I and II and ever since, improvements have continued to come along. Let's take a quick look at some of these improvements and when they happened. In 1906 front bumpers were added, but it was not until 1915 that tops and windshields became standard equipment on all American cars. A year later rear-view mirrors, stoplights, and an early form of windshield wiper came along. In 1923, four-wheel brakes were introduced, and 3 years later the first automobile heaters were added. By 1927, hydraulic brakes had replaced mechanical brakes, and in 1929 the first car radios were introduced along with dimmers for headlights. In 1937 the gearshift lever was moved to the steering column. That same year saw the introduction of the first automatic transmission. After the war ended, power steering was invented and wrap-around windshields were added for better vision. In the early 1960's seat belts were introduced for safety.

Water bath

Water Bath is a bath of fresh or salt water, as distinguished from a vapor bath. In chemistry, a copper vessel, having the upper cover perforated with circular openings from two to three inches in diameter. When in use it is nearly filled with water, which is kept boiling by means of a gas burner, and the metallic or porcelain basin containing the liquid intended to be evaporated is placed over the openings mentioned above.

Waterfall

Waterfall, or Cataract, is the fall or perpendicular descent of water from a stream or river, found mostly in mountainous regions. It is usually the result of a geológica! upheaval in which ¡mínense masses of rock were shifted hundreds of feet from their former position. In geologic time whole areas were thus elevated and others depressed, and in favorable locations where the fault was abrupt, waterfalls were formed. Subsequent changes resulted from erosion of rocks of different hardness. A remarkable series of waterfalls exists along the inward edge of the Atlantic coastal plain, in the neighborhood of the cities that lie between Trenton, N. J., and Augusta, Ga. Mountain cataracts or cascades make the highest waterfalls. Some of the most important waterfalls and cataracts are: The Falls of Yosemite in California, over 2,500 feet, the highest in the world; the Oroco Falls at Monte Rosa, Switzerland. over 2,000 feet; Victoria Falls in Africa, over 420 feet; Niagara Falls, 165 feet, and Iguassu Falls on the Iguassu River, which separates Argentina and Brazil. In high water the Iguassu Falls are greater in volume than Niagara Falls and are much greater both in height and width; the Gavarnie Falls in the Pyrenees are 1,385 feet; and the Staubbach Falls, Switzerland, 908 feet. Other celebrated waterfalls of the world are: Bridal Veil, Yosemite Park, 620 feet; Chamberlain, British Guiana, 300 feet; Fairy, Rainier Park, 700 feet; Gersoppa, India, 830 feet; Granite, Rainier Park, 350 feet; Illilouette, Yosemite Park, 370 feet; Kalambo, South Africa, 1,400 feet; Multnomah, Oregon, 850 feet; Nevada, Yosemite Park, 594 feet; Ribbon, Yosemite Park, 1,612 feet; Rjukan, Norway, 780 feet; Roraima, British Guiana, 1,500 feet; Skjaeggedalsfos, Norway, 530 feet; Sluiskin, Rainier Park, 1,300 feet; Sutherland, New Zealand 1,904 feet; Takkakaw, British Columbia, 1,200 feet; Vettis, Norway, 950 feet; Voringfos, Norway, 600 feet; Wid-dows' Tears, Yosemite Park, 1,170 feet.

What is a houseboat?

A houseboat is a combination of a boat and a house. Taking a hint from the boat dwellings of eastern Asia, or possibly from the canal boat, the English originated the pleasure houseboat during the nineteenth century. It is a broad, commodious, comfortable affair, consisting of one or more rooms on a flat boat of shallow draft. It is quite popular on the Thames for families or small pleasure parties. The houseboat has been introduced into America. Long Island Sound and the Hudson, the St. Lawrence, the Ohio, the Mississippi, and other American rivers have their fleets of houseboats, which are brought into requisition during the summer months.

What is a Hourglass?

The hourglass is a contrivance for measuring time. In making, the glass-blower closes a cylinder at each end, and draws the walls together to form a small passage or waist at the middle. When complete the glass has the form of two cones placed point to point. In use, as much sand or mercury is inclosed in one end as will run through the passage in an hour. By turning the glass the other end up, the passage of another hour can be marked, and so on. If a person were set to do a task, or wished to speak for an hour, the hourglass reminded him of the passage of time, and also when his "hour was up." Its use gave rise to the expression, "the sands of time." The hourglass continued in use for a long time after the invention of clocks.

Water lily

The water lily is an aquatic perennial belonging to the Nymphacaceae family and including the genera Nyphaea and Nuphar. The water lilies are characterized by a thick fleshy rootstock or tuber which is usually embedded in the muddy bottom of the shallow pond; by large shield-like floating leaves; and by conspicuous ornamental flowers. The flowers are often fragrant and possess beautiful waxy petals. There is a wide range of flower color, white, yellow, rose, red, blue and bronze. The flowers bloom either during the day or night. They include a few outstanding forms such as the lotus flower of Egypt, India and China and the giant water lily, Victoria regia, which grows in the backwaters of the Amazon. The flower of the latter is a foot wide and the leaves are 6-7 feet wide.

The Man with the Iron Mask

|

| Iron mask |

What is isinglass?

|

| isinglass sheet |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)